In the previous post, we explored the differences between machine and human cognition. Now, let's take a closer look at the type of human-like cognition that involves a first-person perspective. By stepping back from the urge to rationalize your thoughts and instead observing how your mind operates, you will see things in a new light.

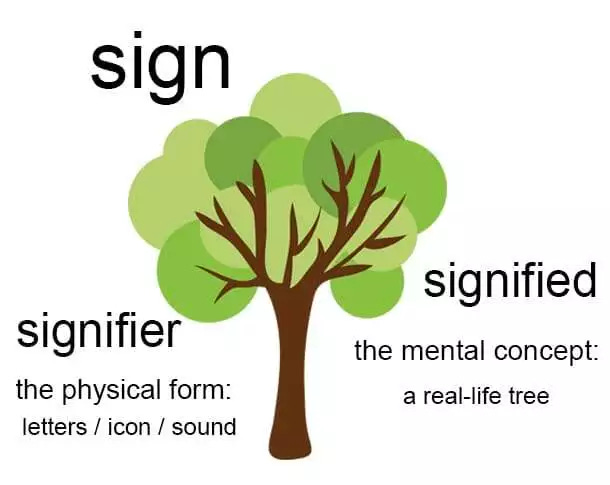

This observation reveals that the process of integration or binding involves a conscious act that diminishes the distinction between the subject and the object of perception. In other words, it reflects a will to identify with the sensed object by re-cognizing, re-capturing, or re-assembling it within myself to become one with it. However, the mere integration of information into a representational unit does not inherently result in conscious experience or semantic awareness. It is through this 're-combination' that my singular sense of self can connect with this integrated unit and unify with it by a ‘seizing of significance.’ It is a ‘thought-conception’ that by a sight takes together the contacted object into the subject. As once Swiss linguist Ferdinand de Saussure recognized, in written text, the syntactic relational structure of the words and their context—the signifiers—coalesce into an evoked semantic unit—the signified—which the mind then internalizes.

Thus, human cognition is a power of consciousness, not the reverse. In living organisms, consciousness does not arise from cognitive processes; rather, it is cognition that requires consciousness. In contrast, cognition devoid of conscious experience is characteristic of machines.

What about cognition in non-human animals? While there is a clear difference in intellectual abilities between humans and, for example, dogs or cats, I believe that these animals also engage in meaning-making processes based on their lived experiences. I do not subscribe to the Cartesian view that regards animals as mere automatons.

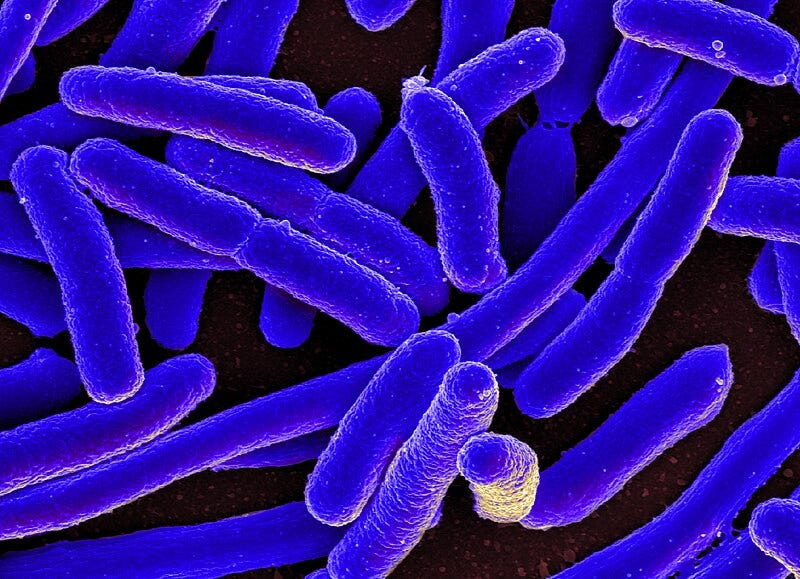

However, as we move down the ladder of biological complexity, the situation becomes less certain. The question arises: Do bacteria ‘cognize’?

As unicellular organisms, their behavior is governed by simple stimulus-response mechanisms that inform them about their surroundings, yet it is difficult to believe they possess any conscious awareness of the environment. There is no entity interpreting the meaning of the signals they process; they lack the semantic understanding that humans, and likely other more complex life forms, have.

What about plants or other organisms without a brain or with only few neurons? In this case also biologists typically view the behavior of plants, jellyfish, and insects as a manifestation of machine-like basal cognition. This perspective is grounded in biochemistry, genetics, physical processes based on thermodynamics, homeostasis, bioelectric signaling, or more recent biological concepts like, complex system dynamics, autopoiesis, free energy principles, etc. It reflects a naturalistic understanding of life as a machine, a viewpoint that has been ingrained in our thinking for about four centuries. This worldview may be the fallacy behind decades of debate on how to define cognition. It may take a considerable amount of time, possibly generations, for us to learn to appropriately contextualize the mechanistic aspect of Nature.1 A perspective that is not inherently incorrect, but can become misleading when regarded as the only valid viewpoint.

As a matter of fact, we can envision simple organisms exhibiting basic forms of cognition alongside simple, basal experiences. Rather than explaining cognition through a reductionist, bottom-up approach2 that views it as a mere product of unconscious, insentient, machine-like problem-solving processes, we should consider the hypothesis that even the primitive sensing and instinctual reflexes of a paramecium coexist with a fundamental, proto-conscious form of sentience. This perspective could provide greater explanatory power. There may not only be an elemental form of sentience but also a basic form of meaning-making—what we might call 'proto-semantics'—that connects entirely unconscious and insentient mechanical processes with the simplest instances of conscious and sentient signification.

Viewing things from this perspective may help us bridge the gap between a mechanistic understanding of life, which constructs complex organisms from a bottom-up assembly of insentient agents acquiring knowledge solely from physical information, and that of a sentient living organism, where ‘proto-knowledge’ is inherently rooted in ‘proto-semantics.’ The deeper ‘understanding from within’ that characterizes human meaning-making might be involved in the fundamental basis of all cognitive processes, even down to the bacteria, rather than an emergent function. Knowledge could be a fundamental power of consciousness, rather than merely the outcome of intricate, blind mechanistic physical interactions.

Seeing the universe as a living entity could enhance our understanding. Matter may be viewed as a concealed form of life, while life itself could represent a hidden aspect of mind. Using the same reasoning, we might conjecture that the mind acts as a hidden expression of a supermind that has yet to be fully revealed on Earth, but is latent and waiting for the right moment to manifest. And, the vital principle in life might not be mere superstition, but rather a reality that science overlooks and vehemently rejects. Life, consciousness, and cognition could be three facets of the same phenomenon. For more technical details, you may want to read my article here.

In other words, we do not try to explain consciousness, cognition, and the mind by starting from microscopic, unconscious, and non-mental processes. Instead, we view consciousness as fundamental, with cognition serving to integrate conscious experiences, and the mind synthesizing these cognitive acts into what we commonly refer to as a ‘thought.’ While we should avoid conflating mind and consciousness, we can loosen the strict distinctions between consciousness, cognition, and mind, considering them as points along a continuous spectrum rather than as entirely separate categories.

If so, this has far reaching implications.

If we consider consciousness as the foundation of cognition and semantic awareness, rather than beginning with unconscious mechanistic processes that supposedly lead to them, this shift has significant implications for AI and the prospects of artificial general intelligence (AGI). Human understanding stems from conscious experience and cannot be reduced to a mere insentient algorithm. Similarly, a human-like AGI must, by definition, rely on a form of cognition that goes beyond simple best guesses, next-token predictions, or high-dimensional vector manipulations. If true semantic understanding requires conscious experience, then any future AGI will also need to possess consciousness.

This is not to say that AGI is impossible or that intelligent machines will never exist. However, it suggests that consciousness may be a necessary ingredient for machines to achieve AGI. While the advent of LLMs has significantly advanced machine intelligence, there has been no progress in making these machines conscious. ChatGPT and similar systems are undoubtedly impressive, but upon closer inspection it is doubtful that they possess semantic awareness. They still do not possess the generality of human intelligence. It may not be coincidental that self-driving cars that rely solely on imagery can easily be fooled and are unlikely to reach level V autonomy. Because a self-driving cars do not understand a thing. It still ‘sees’ only numbers, vectors, and matrixes.3

This viewpoint can be supported with more rigorous arguments; however, to maintain a reasonable length for this essay, I direct those interested in a more technical exploration of this question to my article here.

And, more generally, by comparing AI to living intelligence, we can observe that the most striking difference is not just the difference in cognition, but the absence of essential life aspects. Even the most advanced AI systems lack agency, volition, intentionality, desire, self-reflection, autonomy, and goal-directedness. There is ongoing debate about whether generative AI possesses any creative or original impulse and imagination beyond what it is instructed to do by humans and the data it has absorbed from various sources. If a chatbot is not given input, it remains a passive black box, doing nothing. I argue that this lack of activity stems from the same root as its cognitive limitations: Without consciousness there can’t be any genuine agency, will, and intentionality. Instead, if we assume these psychological cognitive qualities as being an expression of consciousness itself, a lot of things begin to make much more sense.

In conclusion, I would like to address one of the potential objections to this viewpoint.

Many of our cognitive processes occur without our conscious awareness. If this were not the case, we would be inundated with an overwhelming amount of information, making life nearly impossible. There is a significant distinction between what we perceive as conscious thought and unconscious cognition.

For example, think of how we can navigate a complex environment—whether walking or driving—almost on ‘autopilot,’ mentally absorbed in unrelated thoughts while still registering what is around us through peripheral vision. This suggests that we can perform meaningful tasks and comprehend our surroundings even without being consciously aware of every detail. It appears that human-like cognition, which implies a true semantic understanding of the environment, does not require conscious awareness.

Moreover, experimental psychology demonstrates that sophisticated cognitive abilities seem to occur without consciousness. For instance, individuals can process semantic content and focus on objects even when masking techniques prevent the information from reaching their access consciousness. In cases of blindsight, individuals who are cortically blind can respond to visual stimuli they do not report to perceive, due to lesions in the primary visual cortex. Remarkably, they can often correctly identify objects that they believe they do not see.

Does this show that understanding is possible in the absence of consciousness?

I believe this conclusion is premature. Our understanding of consciousness is largely based on a superficial first-person experience. What we refer to as 'unconscious' or 'lack of attention' may actually represent another form of conscious awareness and attention—not unconsciousness, but a subliminal, non-reportable type of awareness. We often confuse non or less ego-centered states of consciousness with being 'unconscious' simply because we cannot relate them to our ordinary ego-centered state of awareness. In these states, we may not be genuinely unconscious; instead, we may simply lack mnemonic access to those experiences.

What is it like to be in a conscious state without memory? Are we truly 'unconscious' during dreamless sleep? Are we unconscious during anesthesia? Are we unaware while in a hypnotic trance or sleepwalking?

We do not have definitive answers. Phenomenal consciousness—that is, some form of sentience—can be present but quickly fade within milliseconds. Different layers of consciousness exist, but their content may not be transferred among them. Consciousness-mediated semantic cognition might still function in these altered states. Therefore, we should avoid making hasty conclusions, as this remains an open question.

Anyway, the main point of this essay is that asking questions about our psychological dimension while trying to detach from a first-person perspective is misguided. The nature of cognition cannot be fully understood from a third-person perspective alone. This approach leads us to begin with unconscious, mindless, and purposeless processes, ultimately leaving us puzzled about how these processes could give rise to conscious, living, and purposeful beings like ourselves. It's like trying to explain cheese while denying the existence of milk, then wondering why it's so difficult to trace its origins.

That’s why, after decades of research and contrived speculations4, cognitive sciences and biology have yet to provide satisfying answers to the deeper philosophical questions surrounding the nature of consciousness, cognition, life, and mind. Ultimately, the process of discovery relies not just on hard facts but even more on our beliefs and thought processes.

The subscription to Letters for a Post-Material Future is free. However, if you find value in my project and wish to support it, you can make a small financial contribution by buying me one or more coffees! You can also support my work by sharing this article with a friend or on your sites. Thank you in advance!

As modern findings increasingly challenge this worldview, many biologists tend to identify themselves as ‘naturalists’ who reject the reductive machine metaphor. However, when pressed, they often resort to descriptions of life that rely on processes, such as complex system dynamics, ‘self-referential feedback loops,’ ‘enactive embodied cognition,’ ‘cellular automata,’ ‘Turing non-computable information processing,’ or whatever concepts that ultimately reiterate the same mechanistic perspective.

Modern findings increasingly challenge the exclusive bottom-up understanding of life as well. In response, many propose theoretical frameworks rooted in the opposite paradigm of a top-down causation. While this perspective is not inherently incorrect, it won’t provide the key to explaining the emergence of cognition, consciousness, agency, and life that they hope for.

Tesla bashing? Yes. :) But I’m sure that other self-driving brands would likely exhibit similar flaws.

To name only few: Autopoietic enactivism, Free Energy Principle, complex dynamical systems theories, predictive processing, Integrated Information Theory, embodied cognition, etc.