The Unexpected Comeback of the Conscious Universe - Pt. III

Modern theories of universal consciousness

Here we go with the conscious universe in all its splendor.

Who would have said that? Until a couple of decades ago almost everyone was certain of the final triumph of materialism. Especially in the neurosciences the mind-brain identity theory was the unquestioned assumption and, de facto, dogma. But things turned out to be somewhat less parsimonious and simplistic than the human mind (or brain?) would like to believe. The hard problem of consciousness was and remains a mystery that seems to have no place in a material universe. And yet, there it is. Especially, since the 1990s scientists were confident that neuroscience would shed some new light. But, when it comes to the deeper questions of more philosophical and spiritual nature it did not lead us further. Not only that, but the universe seems to hide some form of basal cognition in plants and even single cellular organisms—that is, where there is no brain and nervous system to begin with.

That’s why many scientists and philosophers reevaluate some old conjectures about the nature of reality and its relationship with consciousness. To some extent, I would even say, they are reinventing the wheel. The ideas that we are going to study are not new. They framed the whole Indian continent for thousands of years. While Western philosophers like Spinoza, Schopenhauer, Schelling, Hegel, and others speculated about the relationship between God and Nature or the ‘World as Will.’ But trying to connect the dots on both sides and taking into account modern science could furnish a more comprehensive overview. The revival of old metaphysical theories that posit not matter but consciousness as fundamental is a sign of our times. Therefore, let us go through a few of them.

Reflexive Monism

A step forward toward an integral cosmology that can integrate the many ‘isms’ of consciousness studies can be found in the ‘reflexive monism’ of British psychologist Max Velmans1. It rejects reductive physicalism and functionalism. In the simplest terms, reflexive monism is a form of neo-Kantian idealism reformulated with the lens of a modern neuroscientific reasoning (yet maintaining that the noumenon can still be apprehended, against Kant’s claim) and that expands to a cosmology of universal consciousness. It is a map of how the mind relates to the physical world by a reflexive act of perception, emphasizing our instinctive and unaware act of ‘projection’ of our conscious content into the world. Materialist reductionists separate physical objects as perceived from experiences of those objects which are ‘in the brain’. Velmans makes the example of an external observer observing the brain of a subject that sees a light bulb ‘out in the world.’ The reflexive model highlights that the contents of consciousness appear to be ‘out there’ only because it ‘projects’ the experience into a construction we call the ‘3D-space’, and that seems to be beyond the subject’s body surface. What makes the process reflexive is that once the stimuli are processed by the subject’s visual system, the physical processes originating within a light bulb are perceived as light out in the world–that is are ‘reflexed’ outside of the brain. But they are not, because all that we perceive is inside our skull. Similar reflexive loops occur in the body.

For example, a pin prick to the finger activates complex pain circuitry inside of the brain but, nevertheless, results in a feeling of pain located where the prick occurs. This is a sort of reflexive illusion, because the truth of the matter is that all experiences are always situated in us. Reflexive monism recognizes that, at the bottom, all observations can be “objective” only in the sense of being “intersubjective.” Velmans realizes how this has an absurd consequence for reductive physicalism. If an external observer looks at the brain states of someone else, these brain states are only the other’s own brain states. Thus, they cannot provide any information on how and why the subject’s experiences arise, undermining the case for reducing first-person experienced phenomena to third-person observed phenomena. The paradox becomes even clearer once we conceive of the case where one would observe one’s own brain states. There is a lack of conceptual closure between the first- and third-person observation that we cannot bridge, even not in principle. We always have to reflect a sensation or a thought into the world with figures images and figments that are always subjective or inter-subjective.

But one of the main conclusions of reflexive monism, and of primary interest from a cosmological perspective, is that the reflexive aspect of perception also exemplifies a deeper reflexivity in the universe.

Consciousness is compared to an iceberg where our conscious appearances relate to an ‘unconscious ground of being.’ The three-dimensional world that we think of as the “physical world” is only a partial approximation of the greater universe. Human consciousness is embedded in and supported by this greater universe of which we see only a ‘tip.’ The contents of human consciousness are themselves a natural manifestation of the embedding universe. The thing-in-itself is the one universe with relatively differentiated parts in the form of conscious beings like ourselves, each with a unique, conscious view of the larger universe of which it is a part. Human knowledge is one manifestation of a wider reflexive process by which the universe comes to know itself. There is ultimately no separation between knower and known, and knowledge becomes a form of self-knowledge. A form of ontological monism close to the Eastern tradition, or to Huxley’s Mind at large and that anticipated Kastrup’s view of the dissociated alters (see next). An approach that tries to integrate the ‘isms’, by viewing different aspects of the universe as sentient manifestations of itself, from within itself.

Cosmopsychism

Some philosophers of mind, moved by the combination problem of panpsychism, but still intentioned to not fall back to the physicalist standpoint, considered the opposite viewpoint of micropsychism, that of ‘cosmopsychism’, which replaces a bottom-up with a top-down approach and which conceives of the whole cosmos as the ultimate conscious being (see, for example, Itay Shani2).

From this perspective, the Universe is a sort of ‘cosmic Mind’, a unitary conscious entity (something not really new, as it is a concept appearing also in several Eastern traditions). Assuming a universal consciousness as the ontological primitive solves the combination problem because it is the high-level consciousness, rather than the low-level subject, which is the starting point. For example, the human mind, its mentation, and our subjective experiences are a fragment, a localized spot of a much larger cosmic consciousness and cosmic Mind.

If one extends subjectivity not only to matter but also to all space and time and sees the Universe as a ‘super-Subject’, then we don’t need to explain why the bottom-up combination of material objects or particles yields a subject endowed with a unified phenomenal experience—because it doesn't. It is a top-down decombination that does the job, namely, a process of self-individualization of this universal consciousness in space and time by a fragmentation in itself.

This, however, immediately raises the opposite question, that of the ‘decombination problem’ (or ‘decomposition problem’): How do these segments of universal consciousness, what we experience as an individuality, an ‘I’, having private experiences and individual mental contents, come into existence? After all, we cannot (at least not consciously) read each other’s thoughts. If my and your minds are two different specks of a larger Mind, one would expect mind-reading to be part of our everyday experience. Because this seems to not be the case, the cosmopsychist must tackle the opposite problem of the panpsychist and explain how this process of decombination or separation from a universal consciousness yields seemingly isolated individuals with private experiences.

Analytic Idealism

An interesting proposal on how the decomposition problem can be solved comes from the Dutch idealist philosopher Bernardo Kastrup. In his theory of ‘analytic idealism’, also termed ‘Cosmoidealism,’ everything is mental, the inanimate world is an ‘extrinsic appearance of the thought of the cosmic Mind’, what he called ‘Mind at Large’, borrowing the term from Aldous Huxley, and all living organisms are ‘dissociated alters’ of this cosmic consciousness. He was also largely inspired by Schopenhauer and his vision of the world as Will3. Let us look at this in more detail.

Kastrup identifies every experience, be it cosmic or individual, as a ‘pattern of self-excitation of cosmic consciousness’ analogous to modern quantum field theory, which describes every elementary particle as a harmonic oscillator localized in the space and time of a fundamental quantum field. One might even go so far as to question whether it is more than an analogy—that is, one might conjecture whether a quantum particle is indeed the self-excitation of a cosmic entity in itself. In this view, every particular experience corresponds to the particular pattern of self-excitation of this cosmic consciousness.

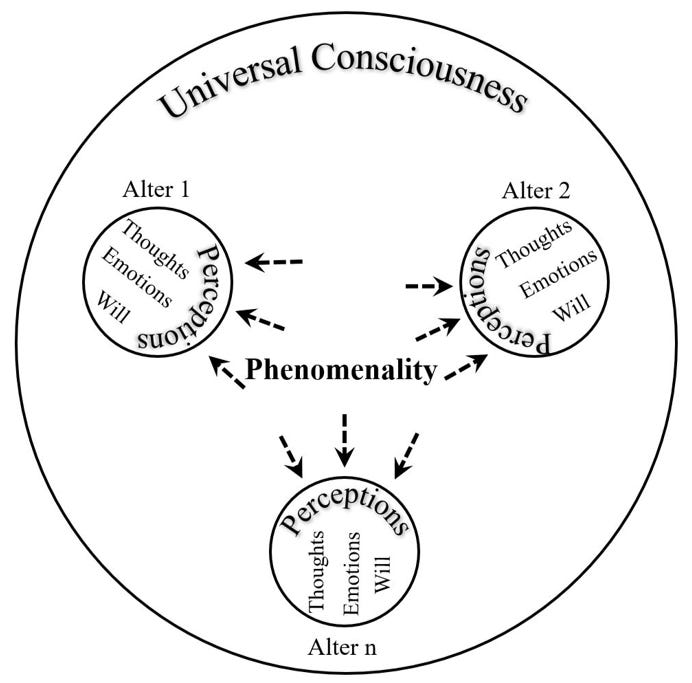

The most curious aspect of Kastrup’s theory is that our ‘discrete centers of self-awareness’, the ‘alters’, arise due to some dissociative process that psychiatrists know as ‘dissociative identity disorder’. A person suffering from dissociative identity disorder exhibits multiple personalities as if the same body contains (or is possessed by) several different subjects with different minds and personalities. Persons affected by this rare state of consciousness, officially recognized as being a real psychological ‘disorder’, exhibit multiple discrete centers of self-awareness. Physically, from a third-person perspective, one sees the same physical body but the individual acts as though driven alternatively by completely different subjects with different personalities.

Kastrup submits that these different subjects—that is, different alters—are not fictional personalities created by a brain disorder but real dissociated centers of awareness caused by the same dissociation process in cosmic consciousness, which leads to the formation of our subjective individuality, the ‘I-ness’ we experience as sentient beings. Our identity as a seemingly separate individual having the illusion of separation arises due to a cosmic dissociation at the mesoscopic level of living beings, between the microscopic realm of elementary particle physics and the macroscopic size of cosmic structures.

Furthermore, Kastrup identifies metabolic systems—that is, our physical bodily boundaries—as the ‘dissociative boundary’ inside which we experience our separate phenomenal consciousness. Metabolic processes in closed biological systems, such as a living cell or a multicellular organism like a plant, animal, or human being, delimit the dissociative boundary between our individualized phenomenal experience and the cosmos from which it has dissociated. This is something on the line of the bounded and self-individuating system of biopsychism, but with the decisive difference that, here, consciousness arises not due to a complicated autopoietic process but rather from a dissociative process in an a priori existing Mind at Large.

In this view, all the matter and the complex structures we observe in the universe are thoughts of Mind at Large. Also, all the physical phenomena we perceive, such as light, electromagnetic, and nuclear forces acting in space and time, are thoughts of this cosmic Mind impinging on our sensorial organs and bodies, the alters’ dissociative boundary. In fact, all our physical senses are mediated by sense organs at the dissociative boundary, which is our body. Kastrup frames the hypothesis that all the qualitative experiences that we become aware of on our 'screen of perceptions’, such as colors, sounds, flavors, textures, etc., are ‘desktop-representations’ of the qualities experienced by a segment of cosmic consciousness. This is to say that our experiences and all the qualia we perceive are not the same qualities that Mind at Large perceives; rather, they are a reduction and figment of it. For example, what we apprehend as a tree with a green leaf is a thought of this cosmic consciousness which it experiences as mental, not qualitative, content. Our experiential qualities are coded representations of thoughts of a cosmic Mind but from the perspective of a dissociated boundary. They do not feel like thoughts at all because of this informational process of reduction and compression that occurs due to us observing through the dissociative boundary.

Finally, in this cosmoidealist view, the cosmic consciousness is not really a self-aware superconscious being that is capable of a higher cognitive process; rather, it is a reactive and instinctive being that does not really have a goal or preconceive a cosmic evolutionary project. It is a sort of borderline between a pantheistic and panentheistic conception of a Spinozian God which, as in Schopenhauer’s world-conception, simply is and acts only by a blind Will that is not self-reflective but grows in its self-awareness by being and becoming in an undirected evolution process. This also answers the question about the existence of suffering in this seemingly unconscious cosmic play. Mind at Large has no moral or ethical values; it is just an instinctive Being that slowly becomes self-aware through painful material processes but can’t do anything other than express and follow its own automatic instinctually.

Panspiritism

Another variant of cosmopsychism, which also envisages all of reality as the expression of a ‘fundamental consciousness’ is ‘panspiritism’, an approach of American psychologist Steve Taylor4. Panspiritism means “all is spirit” or “spirit is everywhere”. In a nutshell, it is a panentheistic conception of the universe with Spirit pervading and flowing through all things.

Fundamental consciousness is still the ultimate essence of all that there is, but there is a distinction between spirit and matter. Matter has its own ontological status and is distinct from spirit. It is not just a ‘projection’ or a ‘mirage’ as the Advaita school teaches, or an ‘excitation’ of a ‘universal Mind’ of the cosmopsychist or analytical idealist; rather, it is a ‘product’ and ‘emanation’ of—and pervaded by—spirit, being at the same time of the same nature of it (sort of another state of the Spinozian fundamental substance). For the panspiritualist, matter is not a purely mental or spiritual entity; it has its own reality, just as the wave is distinct from the ocean or different degrees of solidification and ‘crystallization’ of a fundamental substance are distinct forms of the fundamental substance itself.

However, matter is also pervaded by fundamental consciousness, from which it originated and which flows through all space as well. Therefore, consciousness is in all things, but not all things; molecules, atoms, or particles have their own consciousness or mind, as the panpsychist contends. Non-living objects are not individuated conscious entities but nevertheless are immersed in the workings of the universal Spirit. Only structures having a certain degree of complexity can receive and ‘canalize’ fundamental consciousness into themselves. There is a difference between a universal all-pervading consciousness and things through which this fundamental consciousness is ‘transmitted’ by means of its material structure having an appropriate degree of organizational complexity to receive it. For example, a cell is a sufficiently complex structure that can receive and canalize from its inside fundamental consciousness.

In this sense, a cell, a multicellular organism, or a brain each possesses an interior nature which, however, is not ‘produced’ by the physical processes of the cell, organism, or brain; rather, they are the result of the ‘canalization’ of the all-pervading Spirit in—and through—it. It is this localized inflow of the Spirit that generates an individual consciousness. The Spirit flows into our inner beings via our brains. This is what provides us with subjective sentience by an ‘internal animation’ of an organism—a conception of the flow of spirit reminiscent of the animistic beliefs of the native American culture or the flow of the Holy Spirit in the Christian religion.

Also, mind emerged once a physical structure became complex enough. However, contrary to matter, the mind arises due to the interaction of fundamental consciousness with matter in the brain and is not another state of fundamental consciousness as matter itself is. Only in this sense does panspiritism align with the ‘radio metaphor’ or William James’ prism analogy that sees the brain not as a generator but as a transmissive organ: There is a ‘transmission’ of a cosmic subject via the brain, which, in the material manifestation, is expressed as mind. This means that, for panspiritism, the physical preceded the mental and can exist without it while the reverse doesn’t hold: There can’t be the mental without the physical.

Also, cells, organisms, and all metabolic structures ‘receive’ and ‘canalize’ fundamental consciousness. But there is no evidence that non-living material objects, molecules, atoms, or particles’ receive’ or ‘canalize’ such a fundamental consciousness; therefore, contrary to panpsychism, panspiritism considers them to be non-conscious, inanimate, and without any form of sentient or mental content. In fact, death can be considered the inability of an organism to further prolong its reception and canalization of that consciousness.

This was a quick (admittedly superficial) overview of the most recent and in-fashion theories of universal consciousness.

In the next part, I will make a critical analysis of all the theories we have seen so far, pointing out their strengths and weaknesses, proposing an integral synthesis that integrates them all and goes also beyond them all.

Or…

Thank you for reading my work!

Go to part IV

M. Velmans, Understanding Consciousness, Routledge.

M. Velmans, “Reflexive Monism: psychophysical relations among mind, matter and consciousness,” Journal of Consciousness Studies, vol. 19, no. 9-10, pp. 143-165, 2012.

I. Shani, "Cosmopsychism: A Holistic Approach to the Metaphyscis of Experience," Philosophical Papers, vol. 44, no. 3, pp. 389-437, 2015.

B. Kastrup, "The Universe in Consciousness," Journal of Consciousness Studies, vol. 25, no. 5–6, p. 125–55, 2018.

B. Kastrup, Decoding Schopenhauer's Metaphysics, Iff Books, 2020.

S. Taylor, "An introduction to panspiritism: an alternative to materialism and panpsychism," Zygon - Journal of Religion & Science, vol. 55, no. 4, 2020.

Another excellent overview. I’ve provided several critiques as well as overviews of Kastrup’s MAL (Mind at Large) but I don’t think I’ve seen a better summary and critique than the one you provided here.

Looking forward to the next installment. I hope you submit this series to the Integral Review or some other online publication.