The Mystery of Consciousness and AI

Christof Koch's update, and why he (and we) can do better

The following interview features neuroscientist Kristof Koch, a leading figure in the study of consciousness and a key proponent of Integrated Information Theory (IIT). This conversation is not only insightful as it provides an update on contemporary theories of consciousness, but I also enjoy listening to Koch because he appears open-minded toward the mystical experiences and does not present any preconceived notions of absolute truth. This is the ideal attitude for a scientist to have. Also interesting are the questions and comments of the American cosmologist Brian Keating.

However, to show how we can think about these subjects with an alternative mindset, I would like to emphasize some of their statements and interpretations (see the timestamps) and demonstrate how they are often based on overly simplistic premises or a limited worldview.

2:47 Defining consciousness

Keating’s question of how to define consciousness is a common introduction to the topic. It asks for a third-person characterization of something that is inherently a first-person subjective phenomenon. Many have devoted considerable time and intellectual effort in finding a definition that finds widespread acceptance, but with limited success. The usual instinct is to keep trying until we can establish a characterization that is at least endorsed by the majority of scientists and philosophers. Instead of attempting to articulate something as intangible and ineffable as consciousness, I invite you to reflect deeper on the question of why it is so difficult to express it in words?

In fact, there is a deeper reason why consciousness cannot be defined. When we consider what words ultimately represent—and, more importantly, what they do not represent—the answer becomes almost self-evident. Words signify a state of mind or semantic content that manifests in our conscious experience. Consciousness observes the phenomena of the mind as content displayed on a 'mental screen' in the form of thoughts and concepts. In this way words can only stand for thoughts, concepts, meanings, that are modifications or excitations of consciousness themselves. Attempting to articulate consciousness using words amounts to explaining the nature of water with its own waves. This is why people often find themselves trapped in a logical self-referential tautology, or end up in a ‘strange loop’ when they try to define something with itself. It makes no sense to try to define what can’t be defined even not in principle. Koch is right in guiding Keaton from the third-person perspective to the experiential first-person approach (“Do you hear me?”)

4:28 On “going out of existence” during sleep without dreams

Koch falls into a common fallacy by making an unwarranted assumption about how we supposedly ‘lose consciousness’ in deep sleep—specifically, during dreamless states, comas, or anesthesia. He cites the lack of recall when waking from deep sleep phase as evidence, which is a typical leap to conclusions. This issue is why I addressed it in a recent post.

10:20 The properties of consciousness

According to IIT, Koch identifies specific "properties" of consciousness, such as its specificity, boundaries, structure, and substrate.

Have you ever considered what a "property" means from a first-person perspective? For example, think of a red color, the sweetness of sugar, or the temperature of an object. Every property, even the most physical aspects we associate with the "world out there," is ultimately a subjective experience. This leads us, again, into the same strange loop: in our attempts to define consciousness through its properties, we encounter the same logical circularity that arises when trying to define consciousness itself through words. We rely on the "excitations" of consciousness—these properties—to describe consciousness, as if they exist independently of it.

These flawed and misguided intellectual exercises make me skeptical that IIT will lead to meaningful progress.

12:00 That mathematical structure is conscious experience?

I'm feeling lost here. Claiming that a mathematical structure is conscious experience doesn't mean nothing to me; it sounds like a word salad rather than something meaningful. However, I may be missing something. Please feel free to help clarify in the comments below.

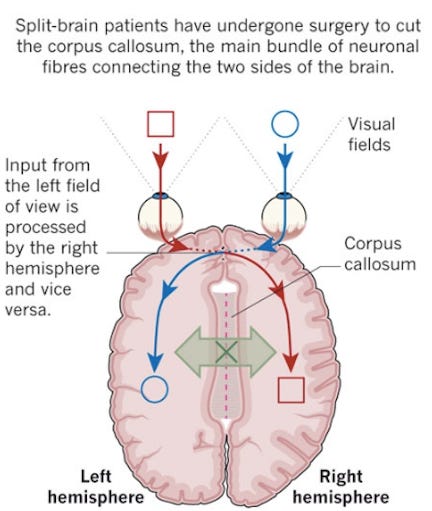

15:03 About split brain patients

The assertion that split brain patients possess two conscious entities within a single body is misguided and has been challenged, with some researchers even claiming to have disproven it. Nevertheless, once certain neurological claims are made by neuroscientists over a period of time, they tend to be accepted as definitive truths that others subsequently repeat. A similar phenomenon occurred with Benjamin Libet’s experiments on free will. For decades, these experiments were regarded as conclusive proof against free will, as they aligned well with the physicalist and determinist perspectives. However, recent findings, free from ideological bias, reveal that neuroscience does not disprove free will.

We are witnessing a similar mindset regarding split brain patients today. The prevailing claim suggests that a split brain indicates a split consciousness, implying that there are effectively two conscious subjects within one body.1 However, there are compelling reasons to question this belief. Nonetheless, people continue to repeat this idea because it fits with their worldview.

What makes people believe in the ‘two subjects one body theory,’ is that some split-brain patients, though a minority, exhibit uncontrolled actions, such as one arm performing an action while the other tries to stop it.2 Additionally, a patient may see something in one part of their visual field but deny its existence because the speech center is disconnected from the visual cortex. However, there are no reports of these patients experiencing a split sense of personhood; they consistently report feeling like a single person, with their sense of self remaining intact. Aside from these unusual behaviors, their parents and friends do not observe anything that might suggest the person is dissociated. This fact challenges naturalists who equate the brain with the mind3, leading them to ignore all this and jump to the opposite conclusions to support their ideological bias.

Anyway, regardless of the truth, I want to emphasize one important aspect: we often conflate and confuse different phenomenal aspects of our identity. There is a distinction between a person and their personalities. One can embody a single persona while possessing multiple personalities. This phenomenon is not only possible, but it is part of our everyday experience.

If this sounds strange to you, consider this from a first-person perspective. Reflect on how you are not a monolithic entity of desires and thoughts. One part of you may long for something, while another part recognizes that pursuing it isn’t safe. You may experience a stream of thoughts that some aspect of you finds uncomfortable. There may be elements of your personality you wish to eliminate, yet they persist because they are beyond your control. You may experience sudden intuitions that conflict with your analytical thinking. We don’t have just one mind; what we call the 'mind' is actually composed of multiple minds, most of which are subconscious or subliminal. Still, you don’t perceive yourself as multiple individuals; your identity and sense of self remain intact despite these varying personalities. In split-brain patients, the lack of control one hemisphere has over the other becomes more apparent; however, this does not suggest the presence of a split consciousness.4 If we continue to confuse these aspects of our psychological dimension, it is largely because we do not know ourselves. Ultimately, this confusion also manifests in the reasoning of high-ranked academics who speak about “two conscious entities” or “independent conscious minds.”

17:43 Imagination in AI

Keating poses the question: Can a computer visualize happiness or the sensation of free fall? Can AI develop new laws of Nature through this kind of imagination, rather than merely assembling language from human-created data?

Koch presents an article claiming that AI can generate hypotheses and novel research ideas, write code, conduct experiments, visualize results, and compile its findings into a complete scientific paper. This article is Chris Lu et al.'s paper.

However, another study critiques Lu’s arguments and evaluates several other similarly hyped claims. It finds that AI systems emulating human creativity are plagued by hallucinations, a lack of content diversity, novelty, and robust reasoning capabilities. Most of the ideas they produce can be found elsewhere, raising potential copyright concerns. The authors warn that “while the latest AI models are largely capable of producing linguistically and artistically creative outputs such as poems, images, and musical pieces, they struggle with tasks that require creative problem-solving, abstract thinking, and compositionality. Their outputs often suffer from a lack of diversity, originality, coherence, and hallucinations.”

This is not to suggest that AI will never achieve full creativity, but we should be cautious about drawing conclusions based solely on one paper, or an authority in the field like Koch, that tell us what we want to hear, while ignoring other studies or opinions that present opposing views. Moreover, I have previously noted in a three-part series that there are compelling reasons to believe that as long as AI remains unconscious, it will never 'cognize' as humans do. Without consciousness, true meaning-making is impossible, and without qualia, there can be no AGI.

Here is a podcast that explains why, despite having access to all the world's knowledge, LLM-based generative AI cannot make its own discoveries and invent new things.

21:02 “Yet they don’t have any state of being, they are like a garbage collector.”

Koch seems not to be aware that his words may disconfirm his previous claims. First, he answers positively to the idea that computer visualize sensations an could imagine new laws of Nature, and then tells us that they do merely assemble language from human-created data. In fact, Keating points out the inconsistency. Einstein’s equivalence principle was the insight of a human genius that relied on an experience, it was based on an imagination of what the subjective sensation of free fall could be. If there is no experience, no qualia—that is, no consciousness—one could never come up with a hypothesis that required it.

At least, I and Koch would agree that an AI based on LLMs alone would never be conscious. Much more is needed to get there.

26:40 The ‘perception box’ serves as an effective introduction to idealism and the concept that we live in a matrix. However, a common misconception is that this matrix is merely a construction of the brain. This is misleading because the brain itself is part of the matrix. Attempting to explain an illusion—a construct of the mind—while using something that is inherently part of the same illusion creates, yet again, a logically circular argument. This may explain why people struggle to grasp the next step: recognizing that consciousness is fundamental. Once you grasp this understanding, your perception of reality transforms, even though nothing in reality has changed.

38:08 On Integrated Information Theory

Koch's et al. IIT, suggests that the integration of information inherently possesses the causal power to 'generate' or 'create' consciousness. I find this perspective on consciousness rather perplexing. It seems to me that, because humans struggle to understand themselves, we flip things upside down.

The integration of information is presented to our 'screen of consciousness' by the mind as a semantic whole. Information integration is an act of consciousness, not a process that generates it. The integration is captured by awareness, but there is no reason to believe that, in and of itself, creates subjective awareness. I have explored this further in my three-part series on cognition. Historically, we were misled by our senses into believing the sun revolved around the Earth. Today, we are similarly misled by our minds, which suggest that the process of integration leads to conscious perception, leading us to believe that binding and integrating information elicits consciousness. This represents the same cognitive fallacy. For additional details on IIT, you can refer to my discussion here.

51:47 Koch’s next book

He intends to write a book exploring the intersection of quantum mechanics, the crisis of physicalism, and the reconciliation of consciousness studies with mystical experiences. However, you don’t have to wait for his book; I have already addressed these topics in my book, “Spirit calls Nature.”

Anyway, the purpose of this post is to highlight that even professionals and leading authorities in the field make assumptions that can be highly questionable. While this is not inherently problematic, it is important for us to be aware of the assumptions we rely on. If we are unaware of them, it is unlikely that we will reach sound conclusions. In other words, despite the significant advancements in neuroscience over the past three decades, particularly regarding deeper philosophical questions, our understanding of the mind and consciousness hasn’t gone much further than what Descartes knew four centuries ago.

The subscription to Letters for a Post-Material Future is free. However, if you find value in my project and wish to support it, you can make a small financial contribution by buying me one or more coffees! You can also support my work by sharing this article with a friend or on your sites. Thank you in advance!

Indeed, a so-called ‘dissociative identity disorder’ exists. However, it is a type of mental condition that is not related to a split brain. In fact, contrary to what one might expect from the standpoint of neuroscience, individuals with dissociative identity disorder do not exhibit any specific neurological anomaly; their brains appear normal. How so?

I remember a funny case involving a split-brain patient who found himself attracted to a nurse. He struggled to prevent his arm from reaching out to her, resulting in inappropriate physical contact that his one-consciousness found extremely embarrassing.

There are lots of neuroscientific facts that undermine this belief as well. You might like to read my article here.

It seems every time I work up a draft and get it scheduled to publish, I see you've just published many of the same points. This time I just finished writing about problems with various definitions of consciousness, how you can't make the part stand in for the whole. Ah well, I'm happy to consider my stuff a supplement to yours. :) Nice work!

BTW, I just ordered your book and I'm looking forward to reading it.

Great text. Maybe a comment on the split-brain theory: it distinguishes two different perceptive approaches to reality: one holistic (right hemisphere), the other detail-focused (left hemisphere). This then gets misinterpreted into saying that the brain has two "consciousnesses" which is absurd, since consciousness is fundamental (or an "ontological primitive"), as you point out. Maybe part of the problem is also terminological as the term 'consciousness' is being used in different contexts with different meanings.

Are you familiar with the work of Federico Faggin and if so, what's your opinion?