The Faculties of Consciousness: An East-West Perspective

Why the five senses may be fundamental rather than emergent

In his essay, Ralph Stefan Weir poses the question: “Why Don't We Study More Indian Philosophy?” Instead of directly answering this question, I would like to provide a practical illustration of how Eastern philosophies—and, more broadly, other non-Western philosophies—can inspire us to expand our mental horizons. By adopting a more integrated approach to knowledge, science, philosophy, and culture, we can enrich our understanding. I will go down this rabbit hole and explore it with a specific example, arguing that the five senses might be fundamental rather than emergent.

According to contemporary theories of evolutionary biology, the five primary senses—sight, hearing, touch, taste, and smell—evolved over hundreds of millions of years as adaptations that helped organisms survive and reproduce in their environments. Their evolutionary origins can be traced back to simple sensory systems in early life forms, which gradually became more complex through natural selection.

Touch is the most ancient and fundamental sense, as it appeared in the earliest single-celled organisms. Primitive life forms, such as bacteria, used mechanoreceptors to detect pressure, temperature, and chemical gradients in their environment. We know that single cells already reach out and touch each other. They respond with ion channels that open on contact, making intercellular communication come alive. Mechanosensitive channels reside not only on the cell’s membrane but also in lysosomes, which are organelles inside the cell. The instinct of “reaching out and touching” something or someone seems primordial and was present from the very beginnings of life. As multicellular organisms evolved, specialized nerve cells developed to process tactile information. This led to the complex somatosensory systems found in modern animals.

Meanwhile, the ability to detect chemicals in the environment was crucial for early life to find food, avoid toxins, and communicate. Single-celled organisms had protein receptors that detected specific molecules—an ability inherited by more complex life. In vertebrates, taste buds evolved to detect nutrients and harmful substances, while olfactory receptors became specialized for detecting airborne chemicals. Smell evolved as an extension of taste, allowing terrestrial organisms to detect volatile chemicals from a distance and thereby boost their chances of survival.

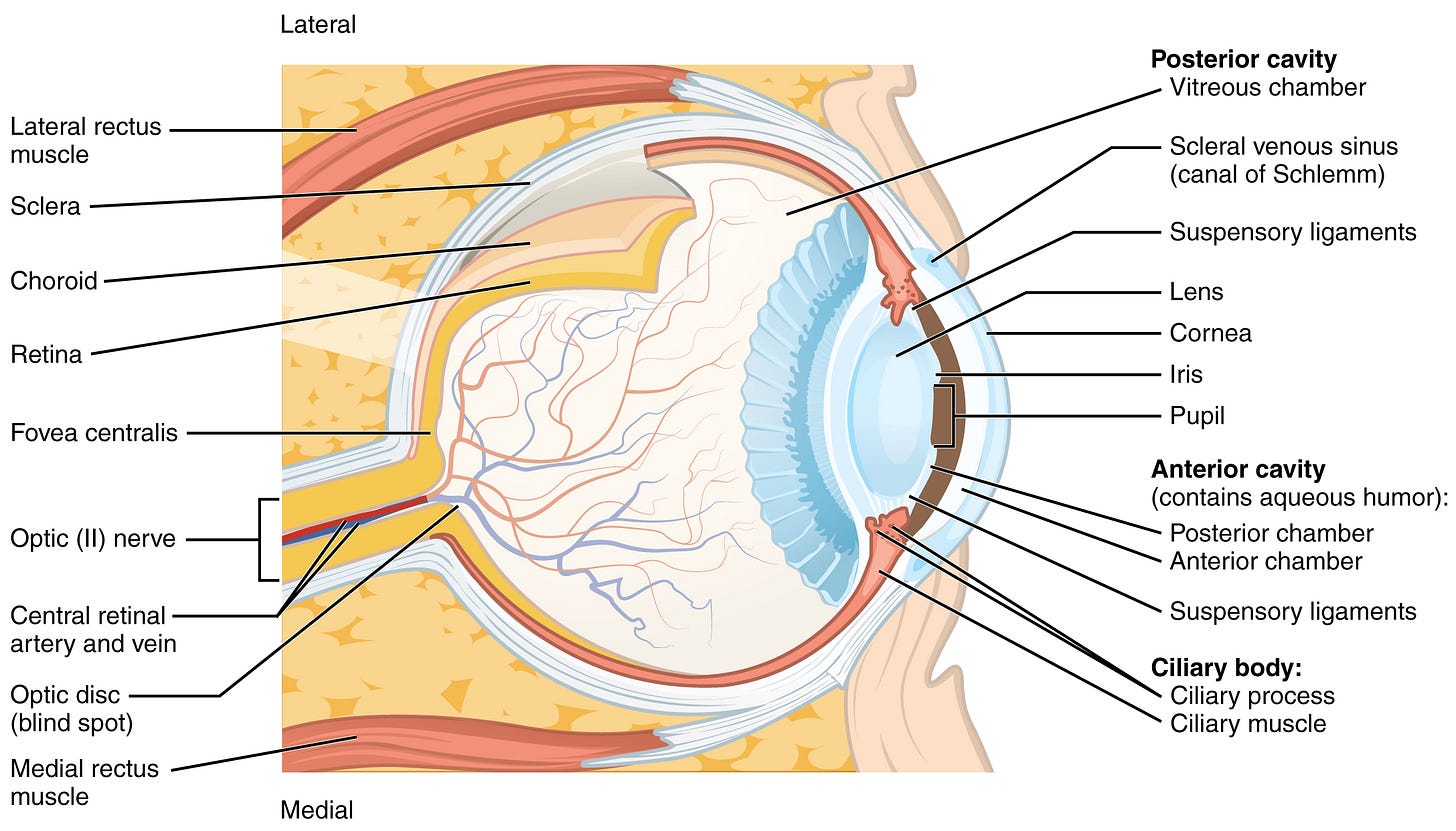

Vision originated from simple light-sensitive cells in early organisms; it helped them differentiate light from darkness. The evolution of the eye began with ancient light-sensitive cells around 600 million years ago. It followed a gradual process, with pinhole eyes evolving into lens-based eyes that allowed for sharp images. Over time, these cells formed clusters, leading to rudimentary eyes in ancient animals like trilobites. Ultimately, it culminated in the sophisticated visual systems found in modern animals, including humans. Different organisms developed specialized vision systems, such as color vision in primates and ultraviolet vision in birds.

Hearing is another complex bio-physical process that converts sound waves into nerve impulses. The evolution of hearing started 250 million years ago along with mammalian evolution, evolving from the faculty to detect vibrations in the environment. Early aquatic animals had simple vibration-sensitive cells that later formed the lateral line system in fish. As vertebrates moved onto land, specialized structures like the eardrum and inner ear bones developed to detect airborne sound waves. Mammals evolved a highly refined auditory system, including three middle ear bones that amplify sound. The sensory cells responsible for hearing, known as hair cells, are located in the cochlea. These hair cells transform mechanical energy from vibrations into electrical signals through a process called ‘mechanotransduction.’ The cochlea contains a basilar membrane that vibrates in response to sound waves, with different regions reacting to different frequencies. These vibrations are then transmitted to the brain via the auditory nerves. Mammals display a remarkable variety of hearing abilities. For instance, elephants communicate using infrasonic sounds, while bats navigate their surroundings through echolocation calls at ultrasonic frequencies. For a nice visualization of the sense of hearing see here.

According to Darwinian theory, these senses provided significant survival advantages, as they allowed animals to detect food, predators, mates, and environmental changes. Over evolutionary time, natural selection favored species with increasingly complex and specialized sensory systems. The result was the wide diversity of sensory abilities seen in the animal kingdom today.

This, in a nutshell, is how modern science describes the fascinating as incredibly complex evolution of our five senses. In other words, science suggests that these senses arose from a lengthy bottom-up process of biochemical and biological evolution.

On the other hand, in the Indian Vedic tradition, people thought the other way around. According to the Aitareya Upanishad, the Self or Atman—the Self-Existing Being—was alone in the beginning. This Being encompassed all the “modes of consciousness,” which were unexpressed and existed only in potential. Not until the primordial Purusha (the eternal Spirit, the consciousness of the cosmic being) projected itself into the manifestation of matter, space, and time did these modes of consciousness emerge as distinct ‘faculties of consciousness,’ as his Word, Breath, Sight, and Hearing.

In other words, while the Veda had no concept of evolution, at least not in the way we understand Darwinian evolution, it did view our physical senses with its sensory perceptions as something imitative of more fundamental aspects of a universal consciousness that have always existed. These faculties of consciousness pre-existed life, corresponded to higher cognitive capacities, and, during the creation of the universe, were cast down and ‘involved’ in matter in the form of physical sensorial senses. The Upanishads specifically envisioned seeing, hearing, and touch as the primary faculties of consciousness, while taste and smell were considered derivatives of these. Rather than being the end result of a complex biological process, these faculties were considered the starting point and inherent qualities of the creative Spirit that brought this universe into existence and projected them in physical embodiments in sense organs as its shadowy and limited sensorial forms, with which we are familiar. However, the true inner senses of seeing, hearing, and touching are not merely the physical sensations we experience in our ordinary state of consciousness; instead, our ordinary sensations echo the Spirit’s true Seeing, true Hearing, and true Touching. They serve as a means of knowledge that connects us only indirectly to the spiritual truths of things and that can be apprehended and comprehended only from a higher level of consciousness.

The rishis, or Vedic seers, categorized the faculties of consciousness into two groups: Seeing and Hearing as perceptive faculties and Mind and Word as their active counterparts. Mind and Seeing are associated with Forms (rūpa), reflecting the aspect of Power, while Word and Hearing are related to Names (nāma), representing the aspect of Knowledge.

When the rishis referred to “Names,” they meant more than verbal labels. “Names” signify powers, qualities, and characters (features and traits that distinguish one thing from another) caught up by our consciousness. These “Names” are latent and inherent in the nameless and timeless Absolute but manifest in the temporal world as the qualities and powers of its earthly forms. Similarly, “Forms” encompass not only signs, words, and symbols but also sound waves, ideas, mental concepts, and even feelings or emotions, all of which are manifestations of consciousness. For example, a specific thought corresponds to a particular 'form' that the mind can adopt.

Thus, Names serve as expressions of Knowledge, while Forms function as expressions of Power. Together, they constitute the phenomenon of Consciousness in manifestation. Through these aspects, Brahman can engage with its creation.

In the post-Vedic period, Sāṃkhya and Yoga viewed the mind (manas) as one of the faculties of consciousness, alongside seeing and hearing, as understood by Vedic and Vedantic seers. The mind was not seen as the product of an evolutionary process; instead, it was regarded as a fundamental aspect of the universe that existed prior to the emergence of life.1

The original theory of knowledge in the Vedic tradition is far more complex.2 However, let's consider whether this intuitive perspective is really so far off from our current scientific understanding.

When I first came across this idea, my Western rational and scientific instincts prompted me to dismiss it as just a religious parable—a convenient fiction from a pre-scientific culture. I believed that the modern theory of Darwinian evolution—based on natural selection and random mutations—is sufficient to explain how life arose and that no other assumptions were necessary. However, over time, my dissatisfaction with the explanatory power of science regarding the nature and origin of consciousness, the mind, and the seemingly teleological character of evolution grew. I found these explanations increasingly, if not superficial, at least incomplete. Moreover, upon closer examination, I realized how one can view, conceive, and understand the scientific and the Vedic standpoints not as mutually exclusive but as complementary.

While there's no reason to doubt the validity of evolution, the key question is whether the mechanisms that evolutionary biology has identified are sufficient to account for the complexity of life. Darwin questioned how complex organs like the eye could evolve through selection alone, especially because they appeared in different species independently. Modern evolutionary biology posits that mechanistic processes of selection can explain the development of complex sensory organs. While these processes undoubtedly contribute, it remains unclear whether they are sufficient on their own to account for the emergence of such complex sensory organs.

While creationists and supporters of Intelligent Design might question this, there is no reason to doubt that natural processes have led to the rich diversity and complexity of life and its organs. However, the idea that adaptation, random mutations, and the ‘sifting’ process of natural selection are alone sufficient to gradually assemble such complex systems is only an assumption, a working hypothesis, and not a scientific fact.

Consider a blind and deaf scientist who lacked sensitivity to touch and who possessed all knowledge of chemistry, biology, and physics 600 million years ago. Not only would such a scientist have been unable to predict the evolution of photoreceptive, mechanoreceptive, and sound-receptive cells into fully formed eyes, ears, and sensitive skin, but the very concepts of sight, hearing, and touch would have seemed completely abstract and devoid of meaning.

It is remarkable how these senses developed almost immediately with the emergence of life, not limited to just one or a few species, but appearing universally across many forms. It was as if evolution felt the need to reinvent the senses multiple times from scratch, starting from an already present and inherent archetypal idea. The emergence of sensory organs seems to reflect a general rule, an inherent power, and fundamental principles of life rather than emerging from processes ruled by mere coincidences.

Furthermore, why should the complex biochemical and bioelectrical processes underlying our sensory perceptions lead to sensations and subjective experiences, ultimately creating the rich, phenomenal world of a sentient being? Of course, here I’m referring (again) to the hard problem of consciousness. Proposing that consciousness and its faculties are fundamental (the Vedic perspective) rather than emergent (the biological perspective) might provide a more coherent theoretical framework with more explanatory power.

Was this also true for the mind, cognition—that is, manas? If so, one should expect brains to develop independently from species to species. In fact, it turns out that birds and mammals did not inherit the neural pathways responsible for intelligence from a common ancestor; instead, these pathways evolved independently. Modern biology interprets this as “convergent evolution”—that is, the independent evolution of similar traits or features in distantly related species, often as an adaptation to similar environmental pressures or ecological niches.

However, we could also adopt an alternative (or complementary) hypothesis suggesting that intelligence might be an inherent aspect of life rather than merely a product of random evolutionary processes. Nature ‘e-volves’ the senses and intelligence from within, whenever and wherever it finds an opportunity to do so, by adaptation, speciation, and natural selection. It is not the other way around.

Moreover, despite all progress, the process that shapes the form of an organism, tissue, or organ—known as ‘morphogenesis’—remains one of the most enigmatic aspects of biology and which cannot be explained solely through genetics and evolutionary biology. We are still far from grasping how a severed salamander limb can regenerate into an identical new limb, how tadpoles can have their heads scrambled yet still rearrange and develop into normal frogs, or how planarian flatworms can be manipulated to grow the heads of different flatworm species without any genetic changes. New ideas and bold hypotheses are needed.

An example I would like to mention is American biologist Michael Levin’s theory of the relationship between morphogenesis and a Platonic space—that is, a latent space of potential forms or pre-existing possibilities that have not yet been actualized.

Levin challenges the conventional paradigm that living beings are solely products of genetics and environment and proposes a framework in which evolution favors forms that exploit mathematical and computational truths. He argues that the relationship between mind and brain is similar to the relationship between mathematical patterns and morphogenetic outcomes, suggesting that cognitive patterns “ingress” from a Platonic space. The theory hypothesizes that instances of embodied cognition ingress from a Platonic space containing both low-agency patterns (like facts about triangles) and higher-agency ones (like mental properties). Morphogenesis is a problem-solving process guided by bioelectric pattern memories. According to Levin, these patterns are derived not solely from genetic information but also from a structured Platonic space of forms. At least some patterns arise from mathematical causes, independent of physical or historical explanations, and are beyond genetics and the environmental constraints, which do not reduce to facts of physics but, instead, exhibit emergent goal-directedness and problem-solving capabilities.

I don’t know how far Levin’s theory reflects reality, but I appreciate that he was bold enough to cross the red line of naturalism and see if and how this could lead us further.

What I strongly sense is that all these natural processes might reflect a deeper creative aspect of Nature, one expressing an even more profound non-natural law of self-expression that transcends them all. By broadening our understanding of life to include, but not be limited to, material, biological, and morphological aspects, we can view the cognitive abilities of all living organisms as manifestations of the emerging faculties of a universal consciousness. From this perspective, many previously unexplained evolutionary processes make more sense.

The Vedic perspective that saw hearing, touching, seeing, name, and form as manifestations of a deeper truth, or Plato’s realm of perfect Forms, might be not just outdated and abstract philosophical fantasies but also intuitions of a deeper truth inherent in reality. I argue that, despite being based on mystical experiences or on the intuitive minds that perceived archetypal realities expressing them with idealist philosophies, these viewpoints can, nonetheless, help us transcend a naïve naturalism. They encourage the intuitive mind to detach from the physical mindset of the naturalist, who believes only in what physical appearances suggest. This shift is desperately needed in our current society, which remains trapped by materialistic thinking and has lost touch with its inner soul.

The subscription to Letters for a Post-Material Future is free. However, if you find value in my project and wish to support it, you can make a small financial contribution by buying me one or more coffees! You can also support my work by sharing this article with a friend or on your sites. Thank you in advance!

One might wonder if we have additional senses beyond the ones we recognize. Perhaps there are subliminal, subconscious, or even extrasensory perceptions of which we're not consciously aware. In the Veda, the faculties of consciousness extend beyond the five senses and the mind to include speech, feeling, and other forms of supra-rational cognition or its expressions. For the sake of brevity, I will focus solely on the former.

For those interested in exploring the subject in depth, consider reading Dr. Vladimir Yatsenko's articles on the “Introduction to the Integral Paradigm of Knowledge,” or “On the Origins of Faculties of Consciousness.”

Excellent, Marco! Well said and thank you for these important insights.

Although a novice reader, this made good points and accessible writing.