Free Will and Determinism: Integrating the Eastern and Western Perspectives - Part II

The Eastern Perspective

In the previous section of this essay, I outlined a Western perspective on the question of free will.1 Here, I would like to explore an Eastern perspective, represented by the vision of the 20th-century Indian mystic and poet Sri Aurobindo.2 In his ‘Essays on the Gita3’ he addressed the question of free will in a couple of chapters entitled “The determinism of Nature” and “Beyond the modes of Nature.”

Sri Aurobindo’s terminology is rooted in Eastern Indian mysticism, and the language, choice of words, and cultural background may not be familiar to the Western reader. Nonetheless, I believe it can powerfully enrich and complement the Western understanding of the world, Nature, and especially ourselves, revealing a much deeper structure of reality. To facilitate the reading, here is a brief overview of the context.

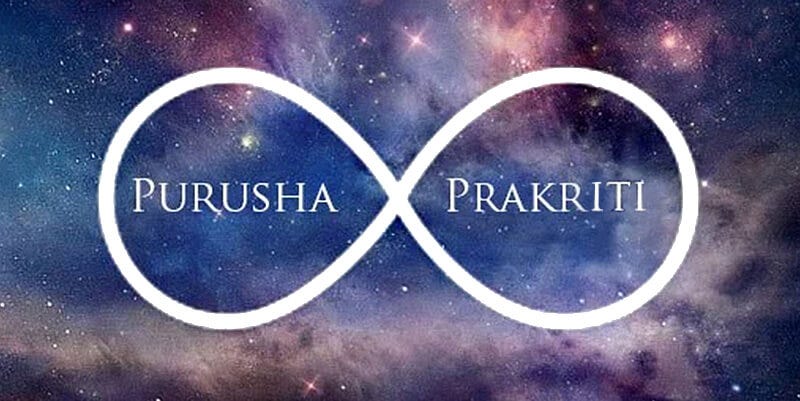

In Indian Samkhya and Yoga philosophy, which also intersects with Buddhist teachings, the relationship between ‘Prakriti’ (Nature) and ‘Purusha’ (pure and basic consciousness, spirit, the true being) is central to understanding the metaphysical framework of the universe. Prakriti and Purusha are regarded as two distinct and eternal principles. Together, they account for both the existence of the universe and our experience of it.

Purusha represents conscious being, the witness and enjoyer of the forms and works of Nature, the unchanging, eternal, and undifferentiated Self. It is the observer or witness of all experience, but, according to the Samkhya, it does not participate in action (something, however, that the mystic experience that transcends the orthodox school of non-duality, tends to disconfirm, as we will see). It is beyond space, time, and causality, existing in a state of pure awareness.

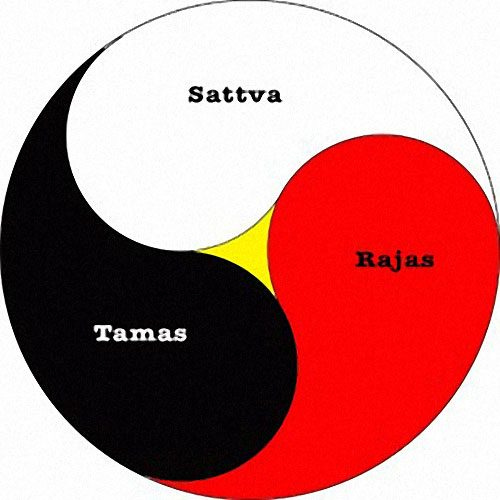

While, the body and mind, are manifestations of Prakriti. Prakriti represents the phenomenal spatial-temporal world and includes everything that is subject to change, including the physical plane (the world of matter, what ordinary science studies) , the mental plane (i.e., the mind and thoughts,) and the vital plane (the world of ‘life energies,’ emotions, feelings.) Prakriti is dynamic and active, and is determined by the three eternal principles, the ‘gunas’ (inherent qualities, tendencies, attributes): ‘sattva’ (balance, equanimity, harmony), ‘rajas’ (activity, passion, restlessness), and ‘tamas’ (inertia, passivity, darkness). Prakriti by itself is unconscious and cannot experience itself. It is through its connection with Purusha that the universe comes into being and is experienced. On the other hand, Purusha by itself without Prakriti, would have nothing to witness. It is when Purusha associates with Prakriti, the process of creation, evolution, and experience begins.

This cosmology is something more elaborate than a Cartesian mind-body dualism. In everyday life, the ‘jiva’ (individual self) tends to identify with Prakriti in the form of a body and a mind due to its ‘avidya’ (ignorance). This identification leads to ‘duhkha’ (suffering), as the self becomes entangled in the cycles of birth, death, and rebirth. The ‘moksha’ (liberation), particularly in Samkhya and Yoga, is to realize the true nature of the self as Purusha and to disassociate from Prakriti. When this knowledge dawns and we are established in the ‘higher Self’, an aspect of ‘Ishwara’ (the supra- and intra-cosmic spirit in the cosmos,) we understand that we are not the body, mind, or the vital, but the eternal, unchanging consciousness, Purusha. Once Purusha realizes that it is distinct from Prakriti and the illusion of ‘Maya’ (the ‘lower Nature’ working in terms of separations and dualities,) one reaches liberation from suffering. The ultimate aim in the spiritual journey is to recognize this distinction between Prakriti and Purusha. While Prakriti continues to exist, the realization of the separateness of Purusha allows the individual to transcend the cycles of karma and samsara, achieving a state of liberation.

Sri Aurobindo doesn’t mince words when making his point.

When we can live in the higher Self by the unity of works and self-knowledge, we become superior to the method of the lower workings of Prakriti. We are no longer enslaved to Nature and her gunas, but, one with the Ishwara, the master of our nature, we are able to use her without subjection to the chain of Karma, for the purposes of the Divine Will in us; for that is what the greater Self in us is, he is the Lord of her works and unaffected by the troubled stress of her reactions. The soul ignorant in Nature, on the contrary, is enslaved by that ignorance to her modes, because it is identified there, not felicitously with its true self, not with the Divine who is seated above her, but stupidly and unhappily with the ego-mind which is a subordinate factor in her operations in spite of the exaggerated figure it makes, a mere mental knot and point of reference for the play of the natural workings. To break this knot, no longer to make the ego the centre and beneficiary of our works, but to derive all from and refer all to the divine Supersoul is the way to become superior to all the restless trouble of Nature's modes. For it is to live in the supreme consciousness, of which the ego-mind is a degradation, and to act in an equal and unified Will and Force and not in the unequal play of the gunas which is a broken seeking and striving, a disturbance, an inferior Maya.

To put it bluntly, the ordinary human state of consciousness is one of enslavement. This doesn’t bode well for our ideas and ideals of free will. It might suggest that we—our small egos—are like puppets, subjected to the absolute and mechanical determinism of Nature, until we learn to live in our higher Self. However, things must be understood in relation to the whole. It is about connecting the dots, or more precisely, uniting the poles into a Yin-Yang relation of duality. How can we reconcile the supposed freedom of the soul with the mechanistic, deterministic, and seemingly unconscious face of ‘apara-Prakriti,’ the lower Nature, and which is a reflection of para-Prakriti, the higher Nature or the true ‘soul Nature’?

A certain absolute freedom is one aspect of the soul's relations with Nature at one pole of our complex being; a certain absolute determinism by Nature is the opposite aspect at its opposite pole; and there is also a partial and apparent, therefore an unreal eidolon of liberty which the soul receives by a contorted reflection of these two opposite truths in the developing mentality. It is the latter to which we ordinarily give, more or less inaccurately, the name of free will; but the Gita regards nothing as freedom which is not a complete liberation and mastery.

What we call ‘free will’ is only partially free. Our true inner self may occasionally offer intimations, suggestions, and, in rare instances, even determine our actions. However, overall, we remain largely subjected to the whims of Nature. Our mental preferences, vital desires, appetites, and instincts—all aspects we describe as ‘my character’—are often just lures and baits of the lower Nature, driving us to actions we mistakenly believe are our own. This psychological perspective is challenging for Western-minded thinkers, who often define ‘free will’ as the freedom to blindly follow and indulge in our (more or less primal) desires and instincts without restraints or distinctions.

But this is only an illusion of freedom, deep down it remains slavery to passions.

What we now call in our ordinary mentality our free will and have a certain limited justification for so calling it, yet appears to the Yogin who has climbed beyond and to whom our night is day and our day night, not free will at all, but a subjection to the modes of Nature.

It is only because we perceive the modes of Nature from a limited mentality, in a state of ignorance, that we misinterpret our bondage to Nature’s movements—such as our desires, automatic (mostly subconscious) thought patterns, emotions, and primitive instincts—as freedom of choice. We like to believe that the impulses of Nature are our own. Caught in attachment to the modes of Nature, we believe we are planning our future and making choices, which, however, are already predetermined by universal forces behind the veil of life’s appearances, causing us—our 'ego-souls'—to behave and act according to a very different plan.

What then is this self that is bewildered by Nature, this soul that is subject to her? The answer is that we are speaking here in the common parlance of our lower or mental view of things; we are speaking of the apparent self, of the apparent soul, not of the real self, not of the true Purusha.

That’s why, when discussing questions of free will, it is essential to ask: who is supposed to be free from what? Are we referring to the freedom of choice of the ego-self or of the higher Self? To use an analogy, what we refer to as 'I' or 'me' represents a 'knot' or small 'vortex' within universal Nature, which can no more free itself from Nature than a water swirl can free itself from water. We mistake our 'desire-soul' for our true soul, without realizing that we are caught in the illusion of what we call our 'personality,' which is composed of desires, appetites, preferences, and tendencies mostly dictated by our social conditionings and past history which, again, make part of Nature’s movements and her gunas as well.

If so, the definition of free will as 'the freedom to make a choice,' which many Western philosophers adopt, becomes highly problematic. The real question is: who or what is free to make that choice—the 'lower self' or the 'higher Self'? Without making this distinction, we almost certainly pride ourselves on our freedom, without realizing that we are merely puppets of forces we are entirely unaware of.

However, where Sri Aurobindo diverges from the traditional view is in the role of Purusha in the divine play, the 'Lila.' The Purusha does not remain an inactive, passive witness forever. As our true inner nature begins to surface and the mind and the emotional being are transformed turning themselves towards the Light of the higher Self, the higher Self starts to influence the deterministic workings of Nature and ultimately takes the lead. Once the soul (not the desire-soul)—our true identity, the 'divine spark'—has grown enough in its evolutionary journey, it increasingly frees itself from the bonds of the otherwise merciless material and mechanical determinism of Nature.4

So too with this truth of the determinism of Nature; it will be mis-seen and misused, as those misuse it who declare that a man is what his nature has made him and cannot do otherwise than as his nature compels him. It is true in a sense, but not in the sense which is attached to it,…

This is a typical understandings of free will defended by several modern scientists. For example, Francis Crick, the discoverer of the DNA helix, once commented: “‘You’, your joys and your sorrows, your memories and your ambitions, your sense of personal identity and free will, are in fact no more than the behavior of a vast assembly of nerve cells and their associated molecules.”5 Stephen Hawking followed the same reasoning: “Though we feel that we can choose what we do, our understanding of the molecular basis of biology shows that biological processes are governed by the laws of physics and chemistry and therefore are as determined as the orbits of the planets.” - “It seems that we are no more than biological machines and that free will is just an illusion.”6 While evolutionary biologists and geneticist Robert Sapolsky doubles down in a podcast: “Not only am I a free will skeptic, I don't believe there is a shred of agency that goes into any of our behavior” (Mindscape podcast, 2021; Sapolsky, 2023).

According to Sri Aurobindo we have to ascend higher and vaster planes of consciousness to avoid seeing things from these lower planes of ignorance of modern science that views these truths from below, “‘mis-seeing” and misunderstanding the determinism of Nature. And how are we supposed to do that? By a self-transcendence obtained with a spiritual practice.

When one has conquered one's self and attained to the calm of a perfect self-mastery and self-possession, then is the supreme self in a man founded and poised even in his outwardly conscious human being, samāhita. In other words, to master the lower self by the higher, the natural self by the spiritual is the way of man's perfection and liberation.

From this cognitive state, the context widens, and Nature’s determinism begins to make sense. Consciousness isn’t a binary on-off state but manifests in various forms, differing in kind and degree. In the atom, it is almost completely concealed by tamas; there is no free will, only mechanical and blind reactions. In the plant, a power of life emerges, but it remains primarily a nervous reaction manifesting a proto-sentience. In the animal, the principle of rajas begins to prevail over tamas, with rudimentary forms of mind and memory. However, it is still largely dominated by Nature and cannot act otherwise. The soul remains a passive witness, unable to influence the being's actions.

It is only in humans that thought can fully develop, intelligent will (buddhi) emerges, and sattwa takes hold, allowing a step toward freedom from the impulses of Nature. While, from this perspective, we are not like animals, we are still struggling with natural passions, desires, mental constructs, habits of a mechanical mind, impulses, and cravings that too often tend to harm rather than serve us. Since we know that our intelligence can, at least partially, help us replace the blind and automatic instinct with a conscious and intelligent choice, we like to believe we are free from Nature’s determinations and that we are making free choices.

However, this too is largely an illusion, as the very same human intelligence, the much-cherished reason and rationality, the bedrock of scientific understanding of reality, that what distinguish humans from animals7, along with our psychological traits and the ego-self we are so attached to, are all creations of the lower Nature as well.8

The buddhi or conscious intelligent will is still an instrument of Nature and when it acts, even in the most sattwic sense, it is still Nature which acts and the soul which is carried on the wheel by Maya. At any rate, at least nine-tenths of our freedom of will is a palpable fiction; that will is created and determined not by its own self-existent action at a given moment, but by our past, our heredity, our training, our environment, the whole tremendous complex thing we call Karma, which is, behind us, the whole past action of Nature on us and the world converging in the individual, determining what he is, determining what his will shall be at a given moment and determining, as far as analysis can see, even its action at that moment. The ego associates itself always with its Karma and it says "I did" and "I will" and "I suffer", but if it looks at itself and sees how it was made, it is obliged to say of man as of the animal, "Nature did this in me, Nature wills in me", and if it qualifies by saying "my Nature", that only means "Nature as self-determined in this individual creature".

And it is here where the entire argument we explored in the previous post gets stuck. It can’t move beyond a partial truth. Indeed, it is Nature that wills and chooses through us, using conscious intelligence (as Kastrup intuits), while the passive, witnessing Purusha remains in the background (as Busstra intuits). But this is far from the whole story. Self-deception is always at play.

When we think that we are acting quite freely, powers are concealed behind our action which escape the most careful self-introspection; when we think that we are free from ego, the ego is there, concealed, in the mind of the saint as in that of the sinner. When our eyes are really opened on our action and its springs, we are obliged to say with the Gita "guṇā guṇeṣu vartante", "it was the modes of Nature that were acting upon the modes."

However noble our desires may be, we are still acting in accordance with Nature, which wills through us. This is what Kastrup realized, yet he found no better solution than to declare an identity between free will and determinism. What he has not yet intuited (or does not consider plausible) is that a higher Nature might lie behind the mask of the deterministic and mechanical second self we perceive. To comprehend the workings of this higher Nature and distinguish it from the lower Nature, a parallel shift in consciousness—from the lower self of ignorance to the higher Self of knowledge—is necessary. Only then can Nature be transmuted from a chain into an instrument.

In other words, freedom, highest self-mastery begin when above the natural self we see and hold the supreme Self of which the ego is an obstructing veil and a blinding shadow. And that can only be when we see the one Self in us seated above Nature and make our individual being one with it in being and consciousness and in its individual nature of action only an instrument of a supreme Will, the one Will that is really free.

Thus, there is freedom, but it lies in the supreme Will beyond Nature. As long as we identify with Nature, our inner true soul—though completely free from Nature—will remain a silent witness in the background while we our behavior and its choices are largely (pre-)determined by forces we aren’t aware of on our surface consciousness. The identity between this false sense of free will and determinism is nearly impossible to refute. However, once we ascend the ladder of consciousness, leave behind all desires, and embrace the supreme Will, becoming “drawn towards it by the highest, most passionate, most stupendous, and ecstatic of all desires,” this seemingly inescapable identification with determinism falls apart.

So, yes, as long as we will not transcend ourselves—that is, misinterpret the shadow we call ‘me’ or ‘I’ for the real Self and real actor—free will will remain an illusion, and the bonds of determinism are real.

And yet, the paradox is that…

The sense of free will, illusion or not, is a necessary machinery of the action of Nature, necessary for man during his progress, and it would be disastrous for him to lose it before he is ready for a higher truth. If it be said, as it has been said, that Nature deludes man to fulfil her behests and that the idea of a free individual will is the most powerful of these delusions, then it must also be said that the delusion is for his good and without it he could not rise to his full possibilities.

It is precisely this delusion that helps us transcend ourselves. This paradoxical, two-sided truth leads, on the one hand, the rational materialist to declare free will an impossibility, with determinism as the only governing law. On the other hand, the introspective individual opposes this idea, relying on an inner feeling that there is something more to us than just a biological robot embedded in a seemingly purposeless clockwork universe. The tension and dichotomy arise because both positions capture only an aspect of the whole, yet fail to see beyond their limited cognitive horizons (and even refuse to admit that there is a horizon at all). Those who are prone to look outward misinterpret matter as the true substance of the universe, while those who prefer to look inward misinterpret their personality, preferences, inclinations, as their true being and the ego's idea of free will as the true will. However, by going beyond both positions and adopting a third perspective, one can see that both approaches are yet another evolutionary trick by which Nature makes us dance.

It is not wrong in thinking that there is something or someone within ourselves, within this action of our nature, who is the true centre of its action and for whom all exists; but this is not the ego, it is the Lord secret within our hearts, the divine Purusha, and the Jiva, other than ego, who is a portion of his being.

The real Self is the Will within, the true master of action. Free will exists, even in the face of Nature's determinism. However, it is not the freedom of someone or, more appropriately, of ‘something’ that is “mastered by pain and pleasure, happiness and grief, desire and passion, attachment and disgust.” Nor is it obtained by the ideas of a mind or the will of the identity we commonly refer to as ‘I’ or ‘me.’ This is where evolution comes into play. It is through the emergence of the true self in the course of evolutionary and spiritual progress that we become aware of our true nature and the real source of our actions.

But a time must come in our progress when we are ready to open our eyes to the real truth of our being, and then the error of our egoistic free will must fall away from us. The rejection of the idea of egoistic free will does not imply a cessation of action, because Nature is the doer and carries out her action after this machinery is dispensed with even as she did before it came into usage in the process of her evolution. In the man who has rejected it, it may even be possible for her to develop a greater action; for his mind may be more aware of all that his nature is by the self-creation of the past, more aware of the powers that environ and are working upon it to help or to hinder its growth, more aware too of the latent greater possibilities which it contains by virtue of all in it that is unexpressed, yet capable of expression; and this mind may be a freer channel for the sanction of the Purusha to the greater possibilities that it sees and a freer instrument for the response of Nature, for her resultant attempt at their development and realisation.

Sri Aurobindo’s writings go much deeper into all this. I'll stop writing about this subject here to avoid making an already lengthy post unnecessarily extended, but I suggest you go through the two essays by yourself.

The essential point I wanted to convey with these two parts is that we can learn (yes, it is a learning process that takes practice and develops over time) to view Western and Eastern perspectives on philosophical and metaphysical questions not as exclusive, but as complementary to one another. Reflecting on Kastrup’s thoughts on free will through the metaphysical lens of Sri Aurobindo allows us to perceive it from a new dimension.

When we realize that the material reality we call ‘Nature,’ which we often see as a blind machine that occasionally gives rise to life on some tiny spot in the universe, is merely a mask for a higher Nature operating from a state of trans-rational knowledge and self-determining power, the troublesome relationship between will and determinism dissolves. If we accept, or at least consider, that our character and personality—with their preferences, desires, instincts, habits, dispositions, passions, and yearnings—are superficial expressions of a lower Nature and have little to do with our true identity, the question of whether the small ‘I’ or ‘me’ is free or not becomes preposterous. Once we recognize that what we perceive as our ‘identity,’ the ‘lower self’ or ‘ego,’ is merely a thought, a fiction, a shadow of our true soul projected by Nature onto the mental plane, we begin to see who is truly bound by determinism and how it can be freed from it.

The Western analytic perspective (of which Kastrup’s reflections are just one modern example) and the Eastern introspective approach of Sri Aurobindo (also just one example) can be seen in an evolutionary perspective. The former helps us take the first steps beyond mere intellectual reasoning into introspection, while the latter transcends the limitations of the mind, leading us further along the path.

The subscription to Letters for a Post-Material Future is free. However, if you find value in my project and wish to support it, you can make a small financial contribution by buying me one or more coffees!

Kastrup’s position is only one of many philosophical theories on the subject, and its content is by no means representative of the entire Western philosophical tradition. However, the analytic methodological approach is. The same is true for Sri Aurobindo’s standpoint, which should not be taken as representative of all Eastern philosophical, spiritual, and religious practices. Both serve only as examples for an East-West comparative study.

Most of the time, Sri Aurobindo is presented as a ‘philosopher’ as well. While several of his writings were expressed in philosophical language, he never considered himself a philosopher, at least not in the traditional Western sense. His vision was shaped by deep mystical experiences, not by analytic or rational thought. On the contrary, it could only emerge from the silence of the mind and the cessation of intellectual activity.

The Bhagavad Gita, or just the Gita, is part of the epic Mahabharata, one of the central Hindu scriptures.

Interestingly, the existence of free will is often denied by non-dual teachers. This is because they have realized the illusory nature of the lower self but have not undergone the process of transformation. Maya has deceived them twice!

“The Astonishing Hypothesis: The Scientific Search for the Soul”, 1994, ch. 1., Scribna.

“The Grand Design,” Stephen Hawking and Leonard Mlodinow, 2010, p.32, Bantam.

I’m not arguing for any moral or ethical superiority of the human animal vs. other animal species. In this context only a cognitive difference is highlighted.

The Buddhist mystics have a lot to tell us about this subject. But I won’t digress…

Excellent integration of contemporary non dual folks, also of Kastrup, in light of Sri Aurobindo.

Living in Sat Chit Ananda