Will AGI Remain Sci-Fi Forever? - Pt. II

And why the AI delusion will teach us a lesson, about ourselves.

The idea of a coming AI revolution is not new. It dates back to the Dartmouth Conference of 1956 in New Hampshire, which was organized to discuss the possibility of constructing intelligent machines. Claude Shannon, the father of information theory, prophetically predicted in 1961: "I confidently expect that within a matter of 10 or 15 years, something will emerge from the laboratory which is not too far from the robot of science fiction fame." During this workshop, the term ‘artificial intelligence’ was coined. In the 1980s, an AI programming language like ‘Lisp’ and its related ‘Lisp machines’ and the supercomputer AI company ‘Thinking machines’ were supposed to open the gates to an AI Eldorado, but were soon absorbed by history; only the older generation or the historians of IT remember it. The Japanese ‘Fifth-Generation-Computer-Systems’, aimed at providing a platform for AI by creating massively parallel supercomputers, didn’t go far and were soon shut down as well. Efforts to create ‘expert systems’ faded because it turned out that they weren’t experts at all. ‘Connectionism’, the science behind the first neural network models, was further developed but didn't meet expectations either. For a while, in a brief ‘AI-winter’, the spirits cooled down, but when the IBM chess-playing computer Deep Blue won against world champion Garry Kasparov in 1997, the hopes of a coming AI revolution were revived. However, by 2001, the intelligent computer HAL 9000, which Arthur C. Clarke and Stanley Kubrick had imagined in their story and film “2001: A Space Odyssey”, was not even nearly in sight. In 2004, DARPA sponsored a driverless car grand challenge and the funding for building automated translation and voice recognition systems skyrocketed. Again, a winter phase followed until 2016, when the program AlphaGo, running on the Google supercomputer DeepMind, won the ancient Go play against world champion Lee Sedol and history repeated itself. New great expectations rose, and the AI-summer was again in full swing, with corporations and governments throwing billions into deep learning neural networks, self-driving cars, and other AI research fields.

We were promised that in a few years, we would have cars driving completely autonomously from the US coast to coast, Skype sessions would have real-time natural speech automatic translation, or IBM Watson—a computer system capable of answering questions posed in natural language—would lead to “cognitive systems that can know and reason with purpose”. These were announced as imminent big breakthroughs and were abundantly hyped in the media with sensational-sounding article titles. Nowadays, nobody is talking about them anymore. These projects not only revealed themselves to be wishful thinking among the popular audience and in the news but they were also endorsed and defended by the majority of professionals in the field. We could read articles full of adjectives and proclamations such as ‘acceleration’, ‘disruptive impacts’, ‘coming revolutions and apocalypses’, ‘breakthroughs’, ‘change of paradigm’, etc., with lots of sci-fi applications, but with no concrete reasons to make one believe that we are anywhere near that. In other words, the border that separates weak AI from strong AI (or AGI) has been shown to be an impenetrable curtainwall of a seemingly unconquerable fortress—a no-progress quest. As I have discussed in my previous post, after almost seven decades of research since the Dartmouth Conference, AI algorithms, or brain-inspired neural network simulations, or LLMs and GPT, there has been almost no progress in building computers able to understand meaning other than by likelihood and curve fitting guessing procedures. Semantics was and remains something utterly precluded to machine learning.

People are now impressed by the almost human dialog with chatbots–that is, AI programs able to entertain an on-line conversation via text or speech. ChatGPTs, of OpenAI officially launched in November 2022. ChatGPT describes itself: “I am an AI language model developed by OpenAI. I have been trained on a large corpus of text data to generate human-like responses to text-based inputs. When a user provides an input, I analyze the input to understand its meaning and context, and then generate a response based on my training and the information I have learned. The training process involved training a deep neural network on a large dataset of text data, where the goal was to predict the next word in a sentence given the previous words. This process allowed the model to learn patterns and relationships in the text data, and to develop a representation of the text that can be used to generate responses to new inputs. Once trained, I can be used to generate responses to a wide range of text-based inputs, including questions, statements, and requests. The quality and specificity of my responses will depend on the complexity of the input and the amount of relevant information available in my training data. In the case of programming, I understand the syntax and semantics of the programming languages and can write programs accordingly.”

Does it really understand the semantics, as it claims?

Anyway, the result is impressive. In a sense, modern technology has almost realized the sort of conversations, in the form of a friendly natural language with robots, that we are so familiar with in sci-fi films. ChatGPT can even generate novel poems and songs and write sophisticated programs. This sparked a debate about whether chatbots could possess some form of conscious awareness. The short answer is no, for the following reasons.

First of all, we have seen how ChatGpt doesn’t understand a thing.

This might sound like a too harsh verdict, considering how LLMs seem to understand in many respects human language. Yet, one can see that the machine does not go beyond a statistical evaluation of what the most likely correct answer possibly could be. While most of the time it does answer correctly and simulates quite well human understanding, often with amazing results that seem to suggest a real AGI, when it fails, it does so sometimes with ridiculous answers. I use regularly ChatGPT, among other things to create some programs. It is amazing to see how it can replace some of the work of a programmer. However, when I asked it to create a very simple algorithm to draw a 5x5 grid, it only produced a non-sensical set of lines. Or when I asked it to count how many zeros and ones are contained in the string “0100011100101010001001001”, it counted 12 zeros and 11 ones, while, as you can check by yourself, 15 zeros and 10 ones is the correct answer. That the answer is incorrect could be seen easily considering that the sum of ones and zeros should be a total of 25 characters, not 23. And, sometimes, I ask the same question in two different ways and obtain contradicting answers.

I don’t get any impression that there is anybody ‘in there’ who understands what it is doing and who can evaluate its own output, realize how it is wrong, and try to amend and improve its answer.

Others made more sophisticated tests. For example, it could be shown that, when a creative task is given, such as designing new rockets, ChatGPT can’t figure out facts and fails to understand basic concepts. This is clearly visible when it designs rocket motors without an engine nozzle or with pipes leading nowhere. Drowning the application with just more data, may fine-tune its skills but will not deliver a semantic agent.

These applications can, indeed, be good information retrieval tools, sort of more sophisticated search engines with a human-friendly interface, but, once again, they are machines that don’t go much further than Searle’s Chinese room or what American linguist and computational linguistics specialists, Emily Bender, called ‘stochastic parrots’. They hallucinate creating combinations of words according to rules they have learned mimicking the human language but remain unable to sort fact from fiction. Despite its very appealing human-likeness, it is doubtful that a system that works like an ‘autofill on steroids’ has any semantic understanding of what it is copying, disassembling, reassembling, and pasting. These AI systems frequently don’t get it right simply because they are not designed to get things right, but rather are built to generate the most plausible answers by trying to predict the next words in the interaction with humans.

Thus, despite all the success of neural networks, LLM, GPT, and other AI-related breakthroughs, I believe that we will sooner or later head again towards another AI winter.[1] To reason over facts something more fundamental is needed. And that is a mind.

The question is whether a subjective experience, consciousness and sentience are necessary for understanding the world? I think that we will ultimately find out that without consciousness there could be no mind as well. This shouldn’t be surprising. That’s how it works in humans.

A congenitally blind person doesn’t know what a color is or could possibly mean because, ultimately, the subjective experience is necessary. Knowledge can’t be reduced to a mere sequence of symbols and syntactic rules, let alone guessing. Knowing always involves some form of experience, perception, sentience, or feeling. You can’t ‘know’ what a sensation, a sensory experience, a feeling of pain or pleasure, an emotion of joy or grief mean at all only by reading about it in a book. You must experience it. Even thoughts are not just a stream of digital bits, they are something that is literally ‘perceived’ by a conscious being in a field of awareness, and that we call the ‘mind.’ That’s why I like to label it the ‘perception of meaning.’ Thoughts are a form of ‘sensory’ experience as well. Because they must be ‘sensed’ by someone who can sense, and make sense of them. It may not be a coincidence that, again, the etymology of words betrays our ignorance. If there is no one having the experience of ‘sensing the sense,’ the algorithm can’t make sense of things, no matter how complicated and advanced it may be.

And, most importantly, what about abstract but for humans very concrete and real concepts, like ‘freedom’, ‘justice’, or ‘beauty’? And what do words like ‘love’, ‘emotions’, or ‘feelings’ mean? These are concepts or sensations that cannot be understood only by rational, logical, linguistic, or propositional analysis, no matter how large and sophisticated the language model is. One can’t understand these things without a subjective experience and without ‘knowing’ what it is like to be in these psychological states.

This implies that a computer will never understand anything unless it has a conscious experience. No matter how complicated, advanced, and super- or hyper- the next generation of AI will be. Consciousness and semantic awareness are inseparable.

Interestingly, however, LLMs show skills in understanding the significance related to lived experiences. Opss… are they becoming conscious?

No, because this is only because sensory relationships are already embedded in language. For example, AI can handle concepts like colors or ‘transparency’ as well as congenitally blind people can do. In fact, blind people can talk coherently about colors or can infer an abstraction of a sensory experience like ‘transparency’ only because they know that others report seeing colors and how they can see through windows. But in what sense is that a ‘knowledge’ or ‘understanding’ of what colors and transparency are?

What differentiates a human being from the best AI models is also the outrageous amount of data that the latter needs to reach comparable skills. A neural network and LLMs need to absorb millions of textual pages, scan all Wikipedia, and must be trained on extremely huge data sets, before becoming able to do what we can do, and have acquired with much less information and training. ChatGPT is not much more than a colossal encyclopedia that crawls the net regurgitating what it finds on its way. It paraphrases information with a bulleted list of facts that can be easily found on the web or elsewhere, not always answering directly to the question and often with a great deal of repetition. It simply parrots lots of tangential information absorbed elsewhere. This should make it clear that something very fundamental is missing when compared to human cognition and, I would add, animal intelligence as well.

Another aspect that is frequently overlooked is the psychological property of all living cognitive and conscious organisms: Will.

Chatbots remain completely passive tools. There is no agency, no will, and no desire to act or create something new. There is no visible sign suggesting that a ChatGPT, or alikes, might possess any internal drive to act, an impulse to autonomously create, or a volition and intention to do something at all, unless explicitly instructed to do so. Otherwise, it is just a passive black box waiting for input. These AI applications are more powerful and elegant symbol-crunching machines, but there is no sign that they will develop any conscious and active self-awareness. There is no reason to believe that anybody is ‘in there,’ let alone a sentient being that understands what it is doing and has a drive to do or create anything.

These were only a few examples of the divergences between machine learning and human cognition. I maintain my skepticism about AGI and find all this talk about the coming revolution of conscious machines ridiculous. It will turn out that deep neural network learning and LLM aren’t deep enough and will be seen as yet another form of computation. Deep learning neural networks, however realistically they might mimic brain functions, will not turn out the magic wand we initially thought it to be. Maybe because it is not the brain that produces consciousness? Of course, so far, this hypothesis remains taboo. It is considered a step too far.

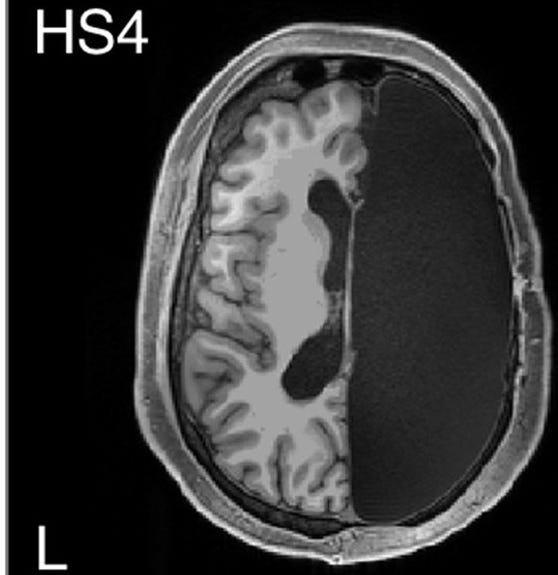

However, you might like to read my research article on the neurological evidence that suggests how our mind-brain identity assumptions could be strongly misplaced. For example you will know about people without half the brain doing well, and many other anomalies that don’t fit into the physicalist narrative.

At any rate, I’m sure that times will change. I believe that sooner or later, the bottom line will be that AI will tell us much more about us, about what our consciousness, our true inner nature, and our psychological and spiritual dimensions are NOT, rather than what consciousness is and how it supposedly emerges by a bottom-up biological and neuronal process. We might get to a point where we will see that, no matter how hard we try and how advanced and sophisticated AI will become, it will always lack what makes us human.

If so, we will be forced to admit that mind and consciousness are not just a mere physical epiphenomenon, and might open our minds toward a post-material understanding of the world. Sometimes the path toward truth is found by exhausting all alternatives. It is a long and hard way of learning things but, once there, this will be the real revolution. And, I believe, much more interesting and fulfilling than any AGI and trans-humanist visions could dream of.

Letters for a post-material Future is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.

[1] For a nice account of the ‘summers’ and ‘winters’ of AI, see the Wikipedia entry ‘History of artificial intelligence’.

Excellent, as always. The persistence of prophecies that we are “just around the corner” from realizing conscious, volitional AI are a striking contrast to what has happened in parapsychology.

For over a century, skeptics have said, decade after decade, “you keep promising scientific proof but you’ve never progressed.”

Now, more than a century after the earliest researcher in parapsychology, everything the skeptics have asked for has been given - well replicated experiments with a large effect size, odds against chance of more than a trillion to one.

So, what do the skeptics say? “Ok, you win, parapsychological phenomena are real and valid.”

There appear to be 2 answers, now that psychic research has progressed to the point where results are as good as that in many other areas of science:

(1) We don’t care what results you have. We don’t even need to look at them, because we know that parapsychological phenomena are impossible based on the laws of nature.

(2) “Ok, yes, you’ve proven psi phenomena, using excellent scientific methodology, beyond a shadow of a doubt. Since we know psi phenomena are impossible, the only conclusion is that science is wrong, and we have to change science.”