I will not take up again here the questions about the environmental emergency, the rapid degradation of our planet's ecosystems, rising global temperatures, the increasingly erratic weather patterns, melting ice caps, wildfires, loss of forests, of ecosystems, etc. We know all too well how this emergency demands immediate and concerted action from governments, corporations, and individuals to preserve our planet for future generations.

Yet, the disconnect between awareness and action remains. While in the news the environmental issues are a permanent topic, the tangible change of consciousness to address them falls short. The paradox is that, as the urgency to mitigate environmental damage grows, the gap between our conception and perception of Nature remains abysmal. The connection is still missing.

On one side, the forces of capitalism, large industries, and corporations are indifferent to environmental concerns. On the other side, ecological movements are striving to make a difference, because they meet with a generalized refusal, not only from these powerful entities or the ruling class but also from a large part of society’s resistance to change, and where consumerist attitudes remain deeply ingrained.

We can see what happens when there is no real collective sentiment and willingness to change things, even if supported by official political declarations. It quickly morphs into a nice wishful thinking that will fail to meet its own climate change targets.

Something is missing. Something is lost. And that is consciousness.

If a conscious connection with Nature were present, we wouldn’t need long discussions about what has to be done. No complicated scientific findings would be necessary to tell us where the problem lies. We would spontaneously know from the inside out. No particular policies would be necessary to convince us to give up some privilege or make a sacrifice to preserve the environment. We would know, feel, and act spontaneously without perceiving it as a “sacrifice.”

But facts on the ground show clearly that this is not where we are. That conscious connection with Nature is missing. It is felt as something other than ourselves. The divide is deep. And it is not just an intellectual divide, but there is a fragmentation in the way we feel and intuit Nature. Let me illustrate this with a curious but also informative example that is not directly related to environmental issues but, in my view, highlights quite well the issue.

From this article in Quanta Magazine (many thanks to

who brought it to my attention) we get to know that scientists discovered how bumblebees are engaged in what could only be described as ‘play.’ Something that had no obvious connection to mating, survival, or reward. In other words, bumblebees engage in the ball rolling for no other reason than humans like to play football, basketball, or soccer.I never thought about insects eventually enjoying playing. However, in hindsight should this surprise us? “Wow… what a great discovery!” I must shout out loud.

First of all, I wonder where comes the idea that only humans play for fun, while all other non-human animals could experience no fun, pleasure, or amusement in playing? According to the materialist mindset, it MUST necessarily be explained away in Darwinian terms. If animals play, that can’t be like for humans. Play serves an evolutionary and a developmental purpose, it offers benefits, contributes to the fitness, survival, and success of organisms, etc. No, it can not be for fun.

Yet, I could ask whether, conversely, this isn’t true for humans as well? If toddlers like rolling a ball, it’s not for fun but because Nature is developing in them the physical traits necessary for hunting, self-defense, and becoming a fit mate. Right?

This latter view doesn’t necessarily contradict our conventional understanding of what playing means and involves; both viewpoints might be true. That play behaviors may satisfy both a biological and psychological function. But why do we always believe that, in animals, it has an evolutionary function only, while rarely think of it in the same terms for humans? After all, such kind of research should not surprise us. If we connect also only superficially with the animal kingdom with a minimum of empathy and detach from our inherent anthropocentric views and feelings (or lack of feelings)—often conditioned by our cultural context and religious beliefs—it should be neither surprising nor difficult to accept that animals like playing too, just for the joy of doing so.

On the same line of reasoning, we read that science is slowly but steadily realizing how consciousness is something much more ubiquitous than previously thought. A group of scientists has now framed a declaration on animal consciousness extending it to a wider range of animals than has been formally acknowledged before.

“Consciousness may also be widespread among animals that are very different from us, including invertebrates with completely different and far simpler nervous systems.

The new declaration, signed by biologists and philosophers, formally embraces that view. It reads, in part: “The empirical evidence indicates at least a realistic possibility of conscious experience in all vertebrates (including all reptiles, amphibians and fishes) and many invertebrates (including, at minimum, cephalopod mollusks, decapod crustaceans and insects).”

Not only your dog, cat, or pet are conscious but also fishes, reptiles, birds, and even insects may have some form of conscious experience!

Really?! Who would have said that!?

Why is it so hard for the human consciousness to accept that also other beings might be conscious? Shouldn’t we realize this as a self-evident fact? Why do we need taxpayer-funded research to find empirical quantifiable evidence telling us this? Wasn’t this already a self-evident fact that we could realize qualitatively, through inner contact with animals, Nature, and all that is living?

There are many possible paths whereby we could gain this intimate spiritual contact with Nature, and that we are so badly missing. In this first part, I would like to approach Nature from a philosophical perspective, while the second part will focus on a more spiritual and almost mystical standpoint.

One entry point might be that of starting from the mind, by progressively shifting to the heart. The first step is to ask what is Nature beyond the technical details you might find in a biology or physics textbook. How often did scientists, philosophers, or philosophically inclined minds ask: “What is Life?” This is a question I already addressed here. But we rarely ask ourselves: “What is Nature?”

According to where we come from and how we think and feel there are several possible answers.

One answer based on a basal instinct, and a survivalist perspective, could be that of stating the obvious: Nature is the resources we rely on for survival, from the air we breathe to the food we eat, and the water we drink. Humans stand at the center of this creation and have the right to exploit its resources whenever and however they like. Unfortunately, this is (more or less unconsciously) the still prevailing conception in a consumerist and capitalist society and is the standpoint that triggers so much surprise when science discovered the curious behaviors of sentient life in the sense I mentioned above.

A slightly broader perspective could be that of the scientist. Nature is that vast and interconnected tapestry of life, encompassing everything from the smallest microorganism to the largest landscape. It is the intricate ecosystems that support diverse plant and animal life, as well as the atmospheric, geological, and hydrological processes that shape our planet and life. Or, going beyond our planetary existence, Nature becomes the cosmos, the physical universe, made of planets, stars, and galaxies that are studied with a strictly empirical and quantitative method. That’s the scientific approach of the physical mind, that kind of limited view of Nature that remains the only one taught in schools and universities. And, unfortunately, it is a trap into which also a large part of the environmentalist movements, which believe that all environmental issues will have to be fixed by mere technological means, have fallen as well. In this technocratic perspective of Nature, I like to dwell for some time myself. But, in the end, I know it is a superficial view, a thin surface of reality, or… well… an intellectual play that might give a satisfaction not so dissimilar to the physical or psychic one that the bumblebee presumably experiences by rolling balls. And, at any rate, it remains insufficient to allow us to go beyond the Cartesian worldview where everything is a mechanical clockwork and every living being is only an automaton. Except for the ensouled human being, of course!

Whereas, an attempt that tries to go beyond the superficial appearances, with a turn within, is that of the poet, the artist, and the esthetician whose desire is to connect with Nature at a deeper level. Then Nature becomes the embodiment of the beauty of a sunset, the raw power of a thunderstorm, or the gentle rustling of leaves in a forest. These feelings then take the shape of a poem, a painting, or a musical composition. It is an inner contact with something concrete that, nevertheless, science tends to dismiss as “just poetry.” It is only in the human imagination, a figment of the mind or our irrational emotions, not something real that makes part of the visible universe. If so, it is strange how many scientists were also artists. For example, Einstein, who played the violin, once said “If I were not a physicist, I would be a musician. I often think in music. I live my daydreams in music. I see my life in terms of music… I get most joy in life out of music.”

Not too disconnected from this perception is that of the natural philosopher. A different but complementary approach of science and arts to Nature comes from a certain kind of continental philosophy. Historically, it was even the first approach to Nature. From Aristotle, who provided a general theoretical framework for the study of Nature in his ‘Physics,’ through Spinoza’s pantheism that equals Nature with God (or God with Nature). Spinoza’s cosmology could be seen as a reaction to Descartes's desacralization of Nature and Francis Bacon’s appeal to literally “torture Nature” to gain knowledge. This creepy analogy was no coincidence: Bacon was also a statesman who actively advocated for the use of torture on humans in legal proceedings as a means “for discovery, and not for evidence”. It was this culture that set the stage for human detachment from the deeper inner realms that inspired writers, artists, and intuitive-minded natural philosophers.

Among the latter ones, of particular interest, I always found Wolfgang von Goethe, the famous German poet, and writer, who developed a phenomenological and non-reductionist approach and way of seeing, a sort of ‘spiritual-mind’ natural philosophy that considers the multiplicity in the unity of Nature and that could become a starting base, or at least a source of inspiration, for a discipline connecting science and intuition. Life is seen from a perspective of unity that explains reality as a whole. Goethe first ‘senses’ the whole and regards the elementary components becoming visible by a top-down approach, not as summing up into the observed reality but, rather, still as the manifestation of that very same whole. While Newton's science looks for the fundamental laws of Nature that govern the manifestation from a microscopic to the macroscopic level of existence, Goethe looked for the ‘primal phenomenon’ (the ‘Urphänomen’) from which all other phenomena can be derived. Goethe’s scientific method is based on this ‘twofoldness’ and applied to natural sciences, which enables us to view it by ‘reading the phenomena in the book of Nature’, as Galileo used to say. But, while Galileo saw this book written in mathematical terms, Goethe opposed the conventional numerical science that analyzes its constitutive components. We should look at Nature like an open book, not by analyzing the single letters it contains, but by silencing our mind and allowing it to capture the significance of the phenomena it conveys. Goethe looked at the qualitative aspect of the world with a more intuitive and comprehensive sight of things, representing the whole by describing it in terms of primal phenomena. Therefore, Newtonian science and Goethe’s conception, or rather “perception” of the wholeness of Nature are not two competing ways; rather, they resort to two different compenetrating and complementary forms of cognition.

Goethe the poet didn't miss the opportunity to express his way of seeing Nature with a poem.

"Nature! We are surrounded and embraced by her: powerless to separate ourselves from her, and powerless to penetrate beyond her. Without asking or warning, she snatches us up into her circling dance, and whirls us on until we are tired and drop from her arms. She is ever shaping new forms: what is, has never yet been; what has been, comes not again. Everything is new, and yet nought but the old. We live in her midst and know her not. She is incessantly speaking to us, but betrays not her secret. We constantly act upon her, and yet have no power over her. The one thing she seems to aim at is individuality; yet she cares nothing for individuals. She is always building up and destroying; but her workshop is inaccessible. Her life is in her children; but where is the mother? She is the only artist, working up the most uniform material into utter opposites, arriving without a trace of effort at perfection, at the most exact precision, though always veiled under a certain softness. Each of her works has an essence of its own; each of her phenomena a special characterisation; and yet their diversity is in unity. She performs a play; we know not whether she sees it herself, and yet she acts for us, the lookers-on." Continues... From “On Nature” - (November 1869) Johann Wolfgang von Goethe

Thus, our exercise to come closer to Nature must be contemplative, not only that of an intellectual ratiocination. We must discover (or should we say “re-discover” and “re-learn”?) how to “see,” not only with the mind but also with the heart and the intuition that apprehends the wholeness of Nature.

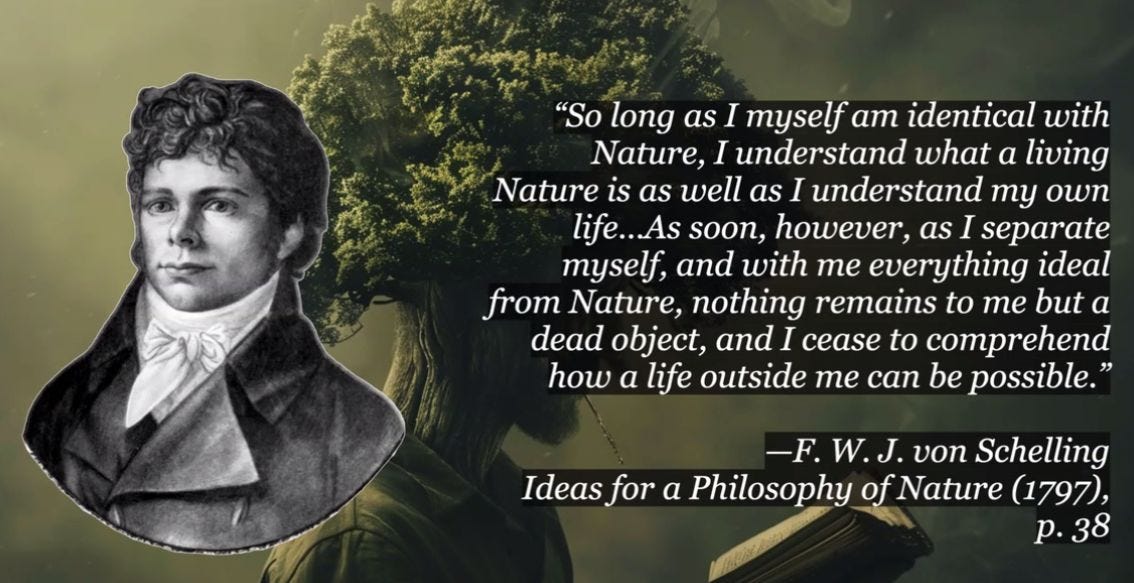

On very similar lines of phenomenological investigation reasoned Joseph Schelling, with an almost spiritual approach to Nature reminiscent of the animistic notion of Nature of the indigenous cultures. His radical choice was to unify Spirit, Mind, and Nature, considering it the different aspects of one unique identity. Nature is the visible aspect of the Spirit, while the Spirit itself hides as the invisible aspect of Nature. Schelling elevated Kant's transcendental idealism to a monistic ontology in which Nature and Reality have an 'original unity' ('ursprüngliche Einheit'), the Absolute. Our separation from Nature renders us spiritually empty because everything is a living being and filled with consciousness.

In his treatise ‘On the World-Soul’ (‘Von der Weltseele’), published in 1798, Schelling recognizes in the human being a somnambulist spirit which, however, is in its essence part of the World-Soul and that identifies itself in the living organism as an object of contemplation. This World-Soul is the universal and all-comprehensive principle in which every soul is integrated. This higher instance is an Absolute that, by seeing itself as embodied, becomes part of Nature and, in it, by successive stages of development, rises in consciousness until it reaches human status. If there is a problem, a tension, or a source between us and Nature, this is due to our sense of separation and lack of connectedness.

Nature and Spirit are two complementary parts of a Whole, in which the latter struggles to become conscious inside the former. All the properties of things in their form, substance, quantity, and quality are different aspects of an internally differentiated 'primordial totality' ('ursprüngliche Ganzheit') in its opposites. What we perceive with our senses and translate in our mind as objects, forms, and symbols are only a partial and incomplete one-sided expression of a dynamic Whole. Schelling envisages the 'World-Soul' as the basis of the whole of reality in which we are, so to speak, embedded and forced to distinguish between a subjective mental world tainted by feelings and perceptions in us, contrasted by what we call an ‘objective world’ outside us. However, this distinction also arises from the internal differentiation of an ‘un-divorced’ Unity (‘ungeschiedene Einheit’) of an absolute-ideal or absolute subjectivity in an ‘eternal act of cognition’. For Schelling, though the essential reality is not accessible to our ordinary reason and mental cognition, we can nevertheless conceive of it as a ‘state of being’ without cognition. This Unity may be cognitively inaccessible to us, but it nonetheless exists as ‘being-in-itself'—or, in other words, is the sole pure state of existence in which perceptions and mind are non-necessary addenda. The Universe is seen as an organism, as a whole containing the organic principles of mind and spirit. The life-principle is immanent in the whole Cosmos. This ‘all-organism’ is the manifestation of the Divine, and all things are contained in this divinity.

Goethe was a poet and a natural philosopher, while Schelling was a philosopher, but none considered themselves mystics. Nevertheless, their approach could help us to go beyond an intellectual apprehension and comprehension of Nature.

Yet, something is still missing. A poetic, philosophic, and sentimental approach to Nature is great, but not enough. It is a movement in the right direction, but still doesn’t go deep enough. Because, after all, it is still a filtration of the Spirit, not its direct contact and realization. We have to go beyond. This will be the theme of the second part.

Yes that article was a good recommendation, wasn't it:>))

That's interesting, the idea of Goethe's view as a higher-mind view (for folks not familiar with the term, the "higher mind" is a term Sri Aurobindo gave for the first of 4 levels of what he called "the spiritual mind."

I had thought the same as you when I came across Henri Bortoft's "The Wholeness of Nature," in which he applies Goethe's phenomenological view to the understanding of nature.

But I later came across a statement by Sri Aurobindo - which, by the way, conflicts with what Satprem, M Pandit and numerous others have said about the higher mind - saying that the essential thing that identifies the higher mind is that there has already been a stable realization of the Self (I know, he doesn't make this clear in The Life Divine; i think it's from a letter he wrote to a student asking about details)

This makes much more sense to me, as it relates to the 'spiritual' mind. We attempted to describe this in the appendix on scientific research of the future which we included in our yogic psychology book. There is at least a sense of the vastness and all pervading nature of pure Consciousness, and possibly a direct "knowing" (knowledge by identity, though not the complete knowledge of the Supermind) of each perceived form as a direct formation of that Consciousness. It seems to me the kind of understanding of morphogenesis and other aspects of evolution would be radically different when everything as seen directly as the Self.