The next evolutionary transition will come from within

Not a clash of civilizations but of two worldviews will remake the world order

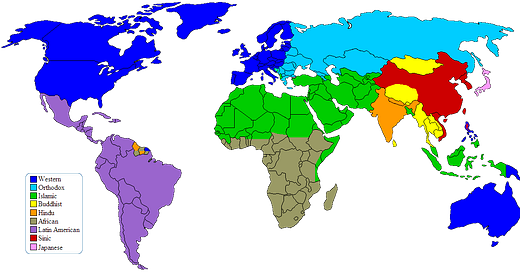

Shortly after the collapse of the Soviet Union, political scientist Samuel P. Huntington famously argued in his book The Clash of Civilizations and the Remaking of World Order that the primary sources of conflict in the post–Cold War world would shift away from economic struggles, competition over resources, ethnic identity, or political rivalry, as seen during the Cold War. Instead, he contended, future conflicts would be rooted in cultural and civilizational differences. Huntington argued that the world is divided into distinct civilizations, each characterized by its own cultural identity, values, and traditions. According to him, these civilizations would become the primary actors in global politics and would inevitably come into conflict due to differences in beliefs, ideologies, and cultural practices. He categorized the world into "major civilizations" such as the Western, Orthodox, Islamic, Buddhist, and Hindu, among others, suggesting that conflicts between these civilizations would replace the ideological conflicts of the past, becoming the dominant form of global conflict in the future.

Critics of Huntington's theory are numerous, and I won’t add another detailed analysis here, other than to note that while he missed the mark, he also intuited an underlying truth. More than three decades later, we can reasonably argue that the real ‘clash’ isn’t primarily among civilizations, religions, cultures, or doctrines but instead between two fundamental perceptions of reality—two worldviews, or Weltanschauungen, that cut across all civilizations, religions, and societies worldwide. This distinction is neither political, historical, nor economic; it is, at its core, psychological, shaping the inner feelings and perceptions of each individual. People may belong to the same nation, family, religion, culture, or civilization, yet inwardly align with one of two opposing worldviews. It is the “polarization” of modern societies that people are talking about. It is this psychological factor that is now shaping social and political power structures, rather than purely external economic or political interests.

The first worldview is rooted in sentiments of solidarity, compassion, tolerance, and empathy, while the second favors egoistic opposition, indifference, and insensitivity toward “the other.”

The first worldview is grounded in an ideal of human unity in diversity, embracing principles of global citizenship, interconnectedness, and multicultural oneness that transcend personal identity. It emphasizes cooperation, mutual aid, solidarity, and sympathy—a collaboration among nations striving for a fair distribution of wealth. In contrast, the second worldview is based on duality, divisiveness, and separation, favoring selfish, nationalistic, and isolationist “my country first” doctrines, which are perpetually focused on self-protection.

The first worldview perceives truth as the foundation of all reality and the inherent spiritual essence of everything that exists. In contrast, the second worldview regards truth as an abstract human construct, something optional from which one can be exempt—placing it on equal footing with falsehood and viewing it as adaptable to serve personal or group purposes when facts don’t align with one’s beliefs.

The first worldview values democracy, the rule of law, human rights, and freedom for all, prioritizing these even above economic and commercial interests. In contrast, the second worldview regards these principles as abstract or of secondary importance, prioritizing economic interests and its own freedom alone. It advocates (more or less openly and unconsciously) a return to a society governed by authoritarianism, where power and “strong men” will finally establish the “lost order.”

The first worldview conceives of humans as an inseparable part of Nature, fostering care for the environment and other non-human sentient beings, and resists sacrificing these on the altar of commercial interests. In contrast, the second worldview perceives Nature, along with all non-human life forms, as something separate and distinct—an inexhaustible economic reservoir to plunder for profit and material gain.

The first worldview is open to long-term change, aiming to transform both outer conditions and itself, exploring new possibilities with a vision and hope for a better future. It embraces uncertainty and the unknown with bold, fearless actions. In contrast, the second worldview seeks to preserve the status quo, avoiding challenges to its comfort zone. It is reluctant to explore ideas beyond a short-term vision and is ultimately rooted in fear and anxiety about what the future might bring.

The first worldview seeks to harmonize the individual, transcending ego-centered interests to align with collective rights and interests. It perceives the individual as a soul and the collective as a "nation-soul," expressing an essential oneness of the universal Self and spirit. In contrast, the second worldview remains entrenched in an ego-centered mentality, viewing itself as a separate, independent being. It places tribal instincts and blood relationships at the center of its universe, seeing others as separate egos to the exclusion of all else. Alternatively, it may also extremize the collective—prioritizing the state and system over individual freedom.

Thus, this polarization is the manifestation of two ways of perceiving and understanding the world that cannot be identified by geographical, national, cultural, or religious lines. It is not a clash of civilizations but rather a conflict between two inner psychological, intuitive, and spiritual forces: one oriented toward spiritual progress, unity, and empathy, and the other rooted in fragmentation and fear. These two contrasting views of reality can be found within the same nation, religion, or even family, as many have recently observed. Little effort is needed to find supporters of both worldviews among Christians, Muslims, Western and Eastern civilizations, political parties, or one or the other nation, etc. Because these two worldviews do not depend on culture, geography, history, or economy. Your decision to adhere to one or the other stream of thought and feeling is determined by "soul factors" that do not depend upon your religion, tradition, or nation.

Let me call the first worldview the ‘cosmic ideal,’ as it represents a movement of consciousness that opens, expands, and integrates all things—especially all beings and Nature—into a unified cosmic vision and sentiment. In contrast, let me call the second worldview the ‘insular ideal,’ as it longs for a return to a past rooted in nationalistic and/or individualistic sentiments of exclusion and seeks to preserve an economic order based on endless growth and the accumulation of wealth through the exploitation of both human and natural resources. Alternatively, we might refer to the supporters of the former as ‘homo cosmicus’ (or the ‘cosmic Christ,’ as T. de Chardin termed it) and those of the latter as ‘homo insularis.’

In this depiction, I’ve portrayed the 'noble ones' as those who embrace the cosmic ideal, and the 'outdated ones' as those still captivated by the insular ideal. However, there are no heroes or champions of righteousness here. We all have internalized, over thousands of years of human history and hundreds of thousands of years of evolution, both worldviews to varying degrees. What I believe distinguishes those who strive for the cosmic ideal from those driven by the insular instinct is not so much the ideal itself, but their inner desire, hope, and at least an attempt to embody it as fully as possible and to integrate it into a vision for the future. Of course, the homo insularis are also souls in development, capable of expressing sympathy, empathy, and commonality with others, including the migrant and “foreigner.” And, like anyone else, they love their children too, as Sting once sang in a not-too-different context. Unfortunately, the latter group still meets the generalization of these ideals across the entire species with resistance and opposition. Deep down, it is the fear of losing one’s comfort zone. On the other hand, while the homo cosmicus has not transcended selfish and animal instincts and can indeed behave insularly, it strives, aims, and desires to rise above human limitations and dreams of a society rooted in ideals of commonality. Ultimately, it is not the intellectual ideal that shapes our behavior, but how deeply this ideal is felt inwardly that makes the difference.

In other words, nobody is perfect. But that doesn’t stop me from asserting that the cosmic ideal is the right path forward, one that will lead us to a more prosperous civilization based on harmony and unity in diversity. In contrast, the insular mindset seeks to reverse the course of history and will ultimately guide humanity toward a world rooted in fear and separation and, ultimately, material and spiritual poverty.

I also believe this will determine the future evolution of humankind. It’s not merely a new phase of history but a transformation akin to the shift from a society without a concept of material progress to one driven by the scientific and industrial revolution. This time, however, the ‘progress’ will be spiritual.

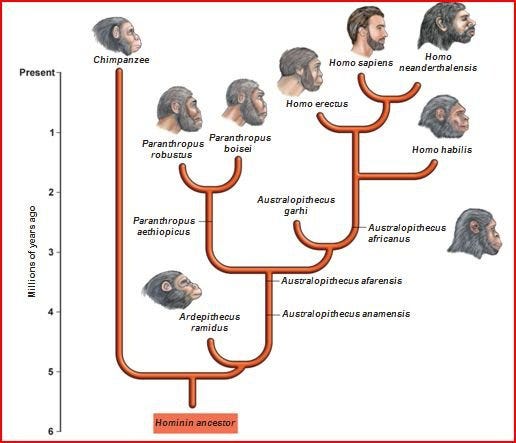

A time will come when people must make a final choice. I’m not sure how much time we have—perhaps a century or two—but eventually, an evolutionary split will occur. This has happened repeatedly in our natural history. There was a time when Homo sapiens coexisted (and even interbred) with Neanderthals. Eventually, one of the two species, the one Nature deemed outdated, had to perish. Neanderthals may not have been a separate species in the strictest sense but could perhaps be considered a different ethnic group, or we might conjecture, a group with a different worldview.

Do not nurture the illusion that this time things will turn out differently. We will not be the masters of our evolutionary destiny. Genetic engineering, transhumanism, AGI, colonies on Mars, or any other naïve and simplistic techno-phantasies will not be the determining factor in our future evolution. The driving force behind evolution will come from within, not from “random mutations.” The decisive factor will not be physical or technological but a “soul factor.” And yet, it will have physical consequences. After all, this is how evolution has always worked, and it will play an even greater role in the future. The time will come when the insular ideal will die out—physically, as well. At this moment, Nature “tolerates” the coexistence of both worldviews, but the evolutionary split will happen, as it always has. The dinosaurs may still dominate the world and even appear highly successful in the present. However, they can only maintain this power because a large portion of the collective remains in a subconscious slumber, allowing them to do so. Their days are numbered, and they will inevitably die out.

The subscription to Letters for a Post-Material Future is free. However, if you find value in my project and wish to support it, you can make a small financial contribution by buying me one or more coffees! You can also support my work by sharing this article with a friend or on your sites. Thank you in advance!

I of course, share your understanding of these two views. I wonder how many, if any, in the mainstream of political/cultural observers see things this way. I hope there are many more, but I'm not aware of any these days. Do you know of any?

By the way, Krishna Prem, in his book "The Yoga of the Katha Upanishad," points out how Sanskrit terms change in meaning over the ages. He states - quite credibly, I think - that around the time of the earliest Upanishads, around 800 BC, "manas" referred specifically to the 2nd way of seeing you describe, point like, based in separation and duality, and "buddhi" referred specifically to the cosmic way, seeing everything rooted in Oneness, Unity.