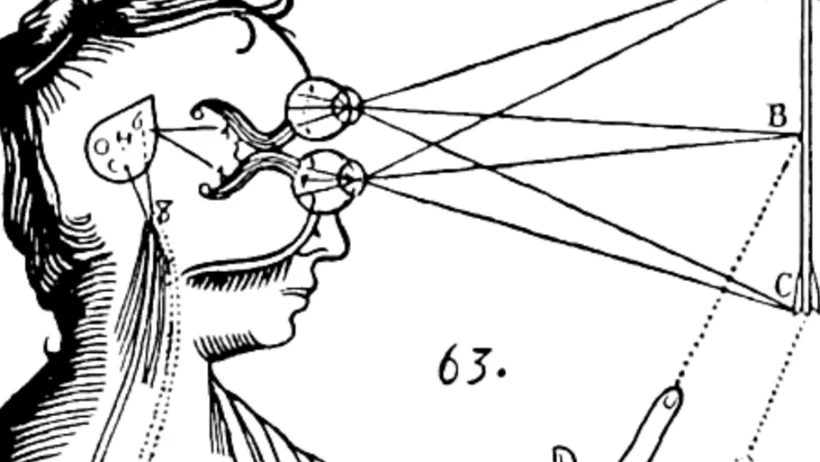

One of the main assumptions of a post-material worldview is that the mind, consciousness, and our mental states cannot be reduced to mere epiphenomena of the brain. René Descartes famously conjectured that the mind is a non-material entity separate from the body, a doctrine that in the modern philosophy of mind is labeled as ‘dualism’, whereby he identified the pineal gland as the seat of the soul. Nowadays, such a simplistic form of dualism has no longer traction, because we know that the pineal gland is an endocrine gland responsible for the production of the melatonin hormone, and there is no reason to believe it could have anything to do with non-material cerebral activities.

Nevertheless, the opposite physicalist doctrine according to which all that we think, feel, perceive, and all that we are, could be reduced to mere biochemical activity in the brain, remains a highly controversial issue among philosophers, scientists, and theologians as well. More sophisticated models than the Cartesian dualism have been developed, and the conjecture that the emergence of consciousness and mind in evolutionary history can’t be pinned down only to strictly material processes in the brain remains a matter of debate.

However, those who contend that mind and matter are intrinsically two different ‘substances’, with the mind being essentially made of something immaterial, always had to confront the so-called ‘mind-body problem of mental causation,’ or just ‘interaction problem’, and which refers to the question how supposedly immaterial mental states could interact with something material, such as a brain? If something is made of some unknown ‘ghostly’ immaterial substance, it is difficult to see how it could interact with something only material, such as the physical neurons making up our brains. Moreover, if something immaterial could interact with material particles, this would conflict with the well-established principles of energy conservation. Because once an immaterial mind would set into motion a material particle, the latter would acquire a momentum (i.e. speed) and a small amount of kinetic energy that would not come from anything present in the material universe and, thereby, would violate the energy conservation principles of physics.

Notice how one could come up with the same objection to speculations involving divine intervention: If God, or a divine cosmic Mind, which we assume to be the very essence of something transcendent and immaterial, would meddle with the material particles in the universe changing the history of an otherwise completely deterministic evolution, it would trigger physical phenomena that violate energy conservation principles. But nothing alike has ever been observed in any experiment and the energy conservation principle remains one of the most solid conceptual bedrocks and empirically certain facts of all science. Thus, the physicalist concludes, that the idea of an immaterial mind or of divine intervention, or whatever kind of ‘immaterial field’ interacting with a brain or any other form of matter in the universe, is inconsistent with the laws of physics, a physical impossibility.

This sounds very plausible and in line with our present scientific knowledge. Right?

First of all, a quick fix to the terminology is necessary. Because much too often we jump to conclusions without being aware that we don’t know what the terms we use are supposed to mean. We use words that we believe to know what they mean, but don’t, and then build upon it sophisticated theoretical castles, and lastly realize that something doesn’t square and turns out to be inconsistent.

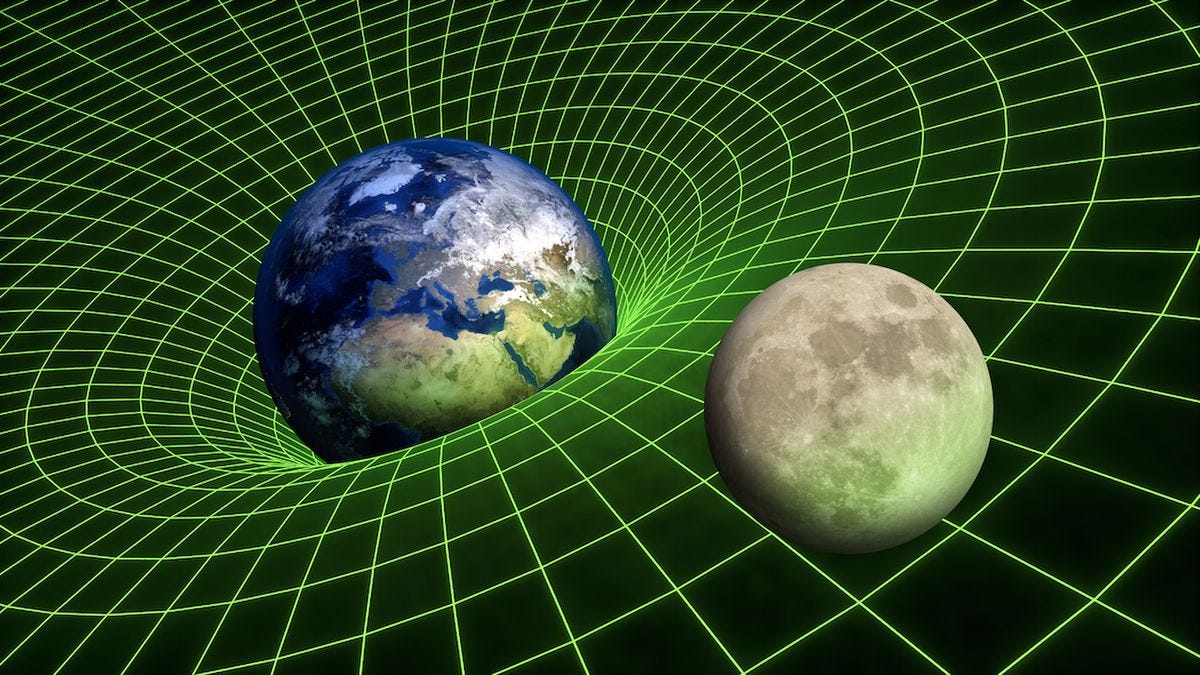

In fact, what does it mean that something is ‘immaterial’? In physics, we refer to material things as anything made of matter–that is, hard stuff made of particles, atoms, and molecules having a mass. But there are a lot of things that have no mass. An electric field, a magnetic field, or more comprehensively any electromagnetic field, such as light, are considered physical entities that have no mass. Light is represented as a particle, the photon, traveling at the speed of… well, of light… throughout space, but having no mass. An immaterial (i.e. massless) electric field can act upon a charged material particle (i.e., having charge and a mass), like an electron. And what about gravity? The gravitational field between the Earth and the moon is a force field that extends throughout empty space without any medium (unlike sound or water waves traveling through a material medium like air or water, respectively.) A gravitational field is massless–that is, an immaterial, yet physical entity that acts upon material things.

Something similar could be said of the nuclear forces acting on the material elementary particles inside the atomic nuclei. And don’t forget Einstein’s mass-energy equivalence represented by his famous E=mc^2 formula that tells us that matter can be converted into energy (typically electromagnetic gamma-rays)—that is, from something ‘material’ into ‘immaterial.’

So, in what sense is the interaction between a material particle with an immaterial field less mysterious than the mind-body interaction problem? Interestingly, however, while very few find the particle-field interaction particularly mysterious, everyone asks for an answer to mental causation.

How does physics explain the interaction between material particles and immaterial fields? Well, it introduces ‘virtual particles’ that pop in and out of existence from the quantum vacuum for a short time that is sufficient to transfer a momentum—that is, mediate a force exchange—between the two particles. The bridge that explains the interaction between ‘material’ particles like electrons and ‘immaterial’ particles like photons is built with other particles that do their job appearing out of quantum fluctuations.

At a more fundamental level, quantum field theory resorts to a model of reality where fields are represented as an exchange of particles again. For example, the electric field causing the repulsion between two interacting electrons is represented by ‘Feynman diagrams as the exchange of momenta by force-mediating massless ‘virtual photons’ between the two massive particles.

In this sense, the description of reality and the interaction between particles by means of the known forces acting at the microscopic level of particle physics (the electromagnetic, and the two strong and weak nuclear forces) is more fundamental: Fields and particles are the two aspects of the same phenomenon. Similarly, at the macroscopic level, it is speculated that also the gravitational field is mediated by gravitational force-mediating particles called ‘gravitons.’

While there is no issue with energy conservation because the massless force particles carry the momentum and energy from one material particle to another material particle. No energy pops in or out of existence, other than during that infinitesimal interaction instant where the exchange of virtual particles occurs.

Thus, physics explains the interaction between matter and fields with a vacuum filled by a fluctuating quantum foam that connects them. If this sounds weird, in a sense it is. But the fact is that this imagery fits well in the calculations with Feynman path integrals, which terms are represented by the iconic scattering diagrams, and that, nevertheless, predict the experimental results extraordinarily well. Physicists are allowed to resort to such absurdities and limit themselves to calculations without asking further questions, as long their theories make testable predictions. It is a model of reality that they adopt because it works and they might tell you “shut up and calculate!”

But from the philosophical and ontological point of view, one might question whether physics has seriously offered a convincing explanation. We don’t know what really these particles and/or fields are beyond an abstract mathematical machinery, and if the distinction between ‘material’ and ‘immaterial’ here makes sense anymore. Physics doesn’t really answer these kinds of questions, it just accepts it as an established fact, formalizes it in a mathematical language, works with the math, and checks if it matches the experimental observations, but doesn’t care much about these subtleties. That is also what led Isaac Newton to spell out his famous sentence “hypotheses non fingo” (“I don’t frame hypotheses”) when asked how an immaterial gravity field could interact through empty space with material bodies. Most physicists will tell you that these sorts of questions are more of a philosophical nature and that we should not try to come up with explanations for those aspects of physical reality.

Curiously, however, the very same insist and pretend for an explanation when the same problem arises in the context of the mind-body causation.

Anyway, let us try to answer the problem of mental causation, nonetheless. We have seen that the above terminology should at least be amended: The mental causation problem isn’t about the interaction between material and immaterial things, but rather between something non-physical (or metaphysical,) and physical. What then distinguishes something ‘physical’ from something else being ’non-physical’?

With ‘physical’ we may mean everything, such as particles, fields, forces, space-time, that could be described by the laws of physics, and measured in a laboratory. If you look up physics textbooks you will not find a definition of what physical vs. metaphysical means. It is assumed as a self-evident notion. One might be tempted to say that everything we can observe or measure with some device and experiment is ‘physical’, while everything else isn’t. Perhaps the best definition I can think of what ‘physical’ means is the following: Everything in space-time that acts through or reacts to forces causing observable material changes.

But such a premise isn’t without difficulties either.

Think of an entity that does not interact with the four fundamental forces of known physics. Is it then, per definition, “metaphysical”? According to the best of our present knowledge, four fundamental forces rule the universe. Namely, electromagnetism, gravity, and the two nuclear forces—that is the strong and electroweak forces. As far as we know no more than these forces are necessary to explain the universe we know. However, there is also nothing in physics that tells us that there can’t be other forces that wait to be discovered. If a fifth force exists and particles interact with each other using this fifth force, then this force and these particles would be by all means ‘metaphysical’ because we have no instruments to detect it and even no clue how to do that, even not in principle. Because all our instruments respond to the known four forces not to any fifth force of which we have no idea. This situation isn’t hypothetical but something that already presented itself in the history of science.

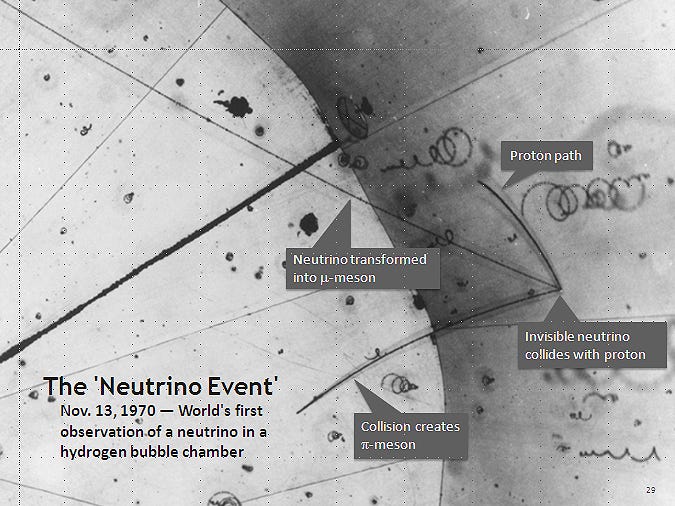

It was the interesting case of the evanescent neutrino particle. Neutrinos interact neither with electromagnetic nor with strong nuclear forces and, thereby, can’t be detected by anything that looks for electromagnetic radiation or is sensitive directly or indirectly to strong nuclear forces. Fortunately, the neutrino particle scatters another particle, say a proton out of an atomic nucleus, by means of (a very improbable but not impossible) electroweak force exchange. That’s why almost all neutrinos that are emitted by the Sun, trillions of which traverse our bodies every second, passing also through the entire Earth completely undisturbed, are so difficult to detect. If neutrinos and protons would not couple to the electroweak nuclear forces at least a bit, as they fortunately do, there could be no way, not even in principle that one interacts with the other and that we could detect the existence of the neutrino. The neutrino particle would be considered something ‘metaphysical.’

Indeed the neutrino was first discovered by an apparent violation of the energy conservation principle. When it collides with a proton we suddenly see a proton being expelled out of an atomic nucleus and becoming visible in the images of the bubble chambers of particle accelerators. The proton seems to be kicked away without apparent reason because neutrinos are completely invisible to detectors that track only protons and electrons and we can only observe the effects that the neutrino produces, never the neutrino itself. That looked like a violation of the energy conservation principle since it was initially unclear where the proton obtained its kinetic energy. Of course, this is not the case, because the energy has only been transferred from a particle invisible to our detectors to another visible particle, the proton. We don’t see the cause but the effect. But the latter can tell us a lot about the former.

This is to say, that it isn’t entirely clear what we mean by non-physical causes having effects on physical objects violating the energy conservation principle. Because what might look like a violation of natural laws might well be the result of our ignorance about other fundamental forces that physics may still have to discover.

But, if so, this makes ‘physicality’ a mere historical notion. Ancient Greece could not know anything about nuclear forces, even not in principle, since its discovery would have required powerful particle accelerators, sophisticated theories, and mathematical tools that were not available at those times. The same could be said about electromagnetic radiation beyond the visible spectrum of the human eye, the existence of atoms and elementary particles or the macroscopic galactic clusters, etc. Did all these things become ‘physical’ only once discovered?

On the Subtle Matter Conjecture

Of course, nobody would believe that to be the case. But this highlights, once again, how the conceptual categories we use, are much fuzzier and more misleading than we might realize. We work with assumptions and imply words having a certain clearcut meaning and semantics that, upon closer inspection, they don’t have. There might be even more intangible particles than the neutrino that couple with unknown forces and that, at this stage, may appear to us ‘non-physical.’ There might exist a form of ‘subtle’ and invisible matter that does not interact with our ordinary matter at all. Because there might be forms of matter that interact with each other via forces that we don’t know to exist. If so, there is a subtle form of matter that traverses our bodies and an entire planet, as neutrinos do, but without interacting with us at all. Indeed, something similar we are nowadays observing with the mysterious so-called ‘dark matter.’ It looks like it interacts only with gravitational forces but is completely unaffected by electromagnetic and nuclear forces—that is, ignores the existence of the kind of matter we are made of. There are good reasons to believe that dark matter, like neutrinos, traverses our entire planet, and our bodies permanently at every second without leaving any trace. We even don’t know if it is matter in the first place.

But the question is: Would a ‘subtle matter’ that does not interact with our matter, because it does not couple to the four fundamental forces, still be considered as something ‘physical’?

Thus, in a sense, the physicalists might be right. There will be never something that is really ‘non-physical’ because it is only a matter of time before our technologies will be able to detect new fundamental forces or more subtle substances that interact with matter, as we know it, only weakly or not at all.

On the other hand, the famous Dutch philosopher Baruch Spinoza might have been right, postulating that everything is only a ‘mode of a Substance’, with that ‘Substance’ ultimately being God. Matter, and anything we label as ‘physical’, is ultimately a ’mode’ (or a ‘vibration’ or a specific ‘state’, if you prefer) of the very same Substance. The dividing line between physical and non-physical would disappear and morph into a continuum, instead of forcing us to make a binary choice. To use an analogy, we could think of a string vibrating with different frequencies. The different resonant modes would manifest with different sound waves, some perceptible and others imperceptible to us. But the substance of the sound waves and that of the string is always the same. It doesn’t change because one produces audible and the other inaudible effects.

This is in line with modern quantum field theories: All particles are the expression of a universal quantum field. Massive and massless particles are only different ‘modes’ of a quantum field. Even the four fundamental forces (the electromagnetic, the two nuclear forces, and gravity) are modeled by force-carrying particles which are represented as vibrations of that quantum field.

That would also solve the energy conservation dilemma. Energy is always conserved but it is continuously transformed from something that we consider being ‘physical’ inside our present paradigm into something that we still consider as ‘non-physical’ (in analogy to the neutrino scattering mentioned above.) But there is no real violation or contradiction. In fact, it might well be that sooner or later we might find evidence for the existence of other fundamental forces other than the four known ones.

Thus, it would be perfectly in line with our present scientific knowledge that the mind works at other levels where a different physics is at work than the one we actually know. For the same reason, some sort of divine intervention a la Spinoza, would not only be possible but a natural state of affairs. Matter (res extensa) is a particular mode of the very same substance we call ‘mind’ (res cogitans.) And mind may again be another mode of consciousness. It is about different degrees of ’subtleness’ of the same thing. Like the solid, liquid, and gas state of aggregation of the same substance.

Not only is this a viable speculative option but seems to be suggested by physics with its description of the world mediated by fundamental forces. Ultimately the distinction between physical and non-physical merges into a foam of forces or, should we say, a network of the action of consciousness.

At the end of the story, the distinction between physical and non-physical or metaphysical is vague and evaporates. Perhaps everything is physical or, equivalently, everything is non-physical or metaphysical. All is a mode of substance, a state of being, a vibratory mode of consciousness.

But why did this argument become so much a matter of debate in the first place?

In my view people are thinking about a completely different issue and that nobody wants to spell out openly. The question is not whether there is a mental causation or not, the real question that people are afraid to say out loud is: “Does the mind, my soul, my consciousness survive the death of the physical body?” This is the real question that people think of when they talk about the mind-body problem.

The answer could be surprising: Yes, also according to our physical theories. Because it is conceivable that the mind exists beyond the body after one’s departure and might be made of a subtle matter that does not interact with the four known fundamental forces. There might exist a universal mental ‘plane of existence’ made of completely different forms of interaction, such as a fifth, sixth, … , n-th force, but that do not couple with the four forces of the material universe we know. However, there might be, nevertheless, an n+1 fundamental force that couples to our ordinary material particles only very weakly—that is, with our body and brain—and with us being empirically unaware because all our instruments couple only to the 1-4 forces (see the neutrino… sort of.) We can conceive of an ontology where everything is ultimately ‘physical,’ and yet part of that ‘physicality’ constitutes a spiritual and immaterial parallel universe where we reside after death. And where all forces, particles, fields, etc., are the different modes of the one Substance.

Of course, this is speculation on my side. But it is almost suggested by modern physics. Contrary to Newton, I believe that framing hypotheses is a healthy practice for doing science and philosophy (by the way, despite his claim, Newton himself did that permanently as well.) What the real solution to the mind-body interaction problem is I don’t know. But the real point I wanted to make, is how all this makes it clear how vague our ideas are about this subject and how unreflectively we speculate about it. Materialists have no point in coming up with the interaction problem presenting it as a knockout argument against dualistic hypotheses or the possibility of divine intervention. But, when asked, one sees how they are usually completely unaware that they don’t know what ‘physical’ or ‘non-physical’ is supposed to mean and never asked the question themselves. This only betrays how they jump to conclusions and have an unreflective ideological bias. While the interaction problem is a valid and legitimate objection, it has by no means the kind of argumentative power that can shut down the conversation, as so many would like to believe. The idea that consciousness, mind, and, I would also add life, are principles that go beyond the ‘physical’ (whatever that means), remains more than ever a viable option. Beware whenever scientists or philosophers invoke the interaction problem as the ultimate, final, and indubitable nail in the coffin of post-material interpretations without further inquiry! It is almost certainly a sign of shallow philosophy based on unreflective thinking.

How could Sean Carroll, more than 10 years ago, claim that "the laws of physics underlying everyday life are completely understood"?

https://www.indy100.com/science-tech/life-after-death-impossible-science-2659472534

His claim seems rather presumptuous. As a physicist, how would you respond to him?