Rediscovering Goethe’s Phenomenology - Pt. II

A first step toward a spiritual science (without science woo...)

Light and Darkness as Primal Phenomena

Goethe also applied his way of seeing Nature to light and the color phenomenon, giving birth to what is known as ‘Goethe’s color theory.’ He considered his theory and his overall approach to optics in stark contrast to Newton's theory of light.

As most of us have learned in school, Newton was the first to show that, by means of an optical glass prism, one can obtain from a white light source the typical rainbow color spectrum, ranging from dark blue, light blue, green, yellow, red, and dark red.[1] Famous is his dark room experiment, also remembered as Newton’s ’experimentum crucis’ (crucial experiment), in which he let sunlight shine through a pinhole in a wall, through an optical prism positioned behind the little aperture, displaying a vividly colored light spectrum—that is, the images of the pinhole itself displaced according to their colors. Therefore, Newton concluded from this experiment that white light must be composed of several different colors. White must be considered a color mixture—that is, a derivative phenomenon emerging due to the combination of the more fundamental phenomena that colors are—but it is not a color in itself. According to this point of view, the prism separates, distinguishes, and differentiates the colors, which, however, should already be considered contained in the white light. The color dependency of the refracting index of the prism causes the colors to be dispersed differently, thereby making them visible to the eye. This idea that white is composed of all the colors of the visible spectrum has been, until today, the commonly accepted wisdom. We get to know that white light can be reduced to the sum of the spectrum colors because the whole (white light) is conceived as the sum of its parts (the colors). How could these empiric facts be interpreted otherwise?

Goethe, however, did not agree and considered Newton's conclusion fallacious. First of all because, from a holistic perspective, one refrains from imagining the whole as the sum of its parts. From this standpoint, the multiplicity of phenomena (the colors) can be thought of as belonging together and as the manifestation of an underlying unity elicited by a primal phenomenon rather than resulting from a process of fragmentation and separation. Secondly, observing the phenomena comprehensively, in order to find the primal phenomenon that reveals it as the multiplicity in unity, means that one should look at it from all its possible perspectives, not limiting oneself to one experiment and viewpoint. We can intuit the primal phenomenon only from the set of overall experiences seen together.

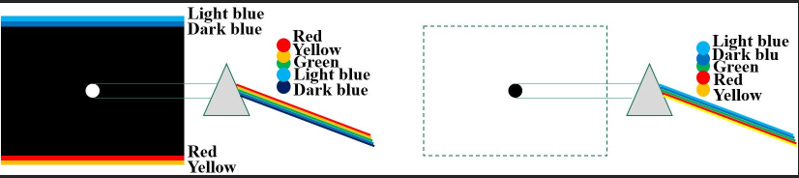

In fact, his counter-argument was that Newton's dark room experiment could also be turned upside down, suggesting the opposite conclusion. Instead of considering a bright spot on a dark background as Newton did (see the figure left), if one observes through the prism a dark spot surrounded by a white background (see the figure right), then one observes a color spectrum arising from the vicinity of that dark spot as well (even though the colors appear in a different order). Specifically, if we are looking through a prism from a pinhole on a dark surface or, on the other hand, a dark spot on a white surface, we will see in both cases the same phenomenon, namely, the circles filled out with colors of the visible spectrum. [2] Therefore, so argued Goethe, using Newton's same logic, we could claim that also darkness is composed of the multitude of colors of the spectrum. Since this is something we could hardly believe to be plausible, Goethe considered this to be proof of Newton being wrong and led him to advance a completely different theory that was supposed to explain the observed phenomena.

Of course, modern optics is capable of explaining the effect of the figure right (as a complicated superposition of white light rays coming from the entire white surface surrounding the black dot and undergoing a wavelength dependence diffraction at its boundaries) but, for the Goethian scientist, it is much easier to think of a phenomenality that comprises both effects—that is, thinking of colors as being the derivative phenomena of a more fundamental one.

Note that the foundation of this different theory relies on an empiric approach that isn’t fundamentally different from that of modern science: a repeated set of experiments which, by precise but comprehensive observations, looks for the most fundamental aspects of it. While Newton looked for the constituents of the observed phenomenon and the fundamental laws governing it, Goethe searched for the primal phenomenon that is capable of explaining all the others—the primordial, primary, or basic phenomenon within which the manifold is to be seen and where all other phenomena can be traced back to its origin.

Thus, for the Goethean scientist, there is not much left in these experiments with the prism other than opting for light and darkness itself as being the primal phenomenon. Goethe’s optical ‘Urphänomen’ is the tension between the polarity of light and darkness. Darkness is no longer considered simply the absence of light but a distinct and concrete entity and universal essence. Light and darkness are not two opposite and separated phenomena but dual aspects of the same entity. This duality is also suggested by the simple fact that we can’t even think of darkness without light, and vice versa. One cannot come without the other, and both must be thought of as a multiplicity in unity.

Unlike Newton’s standpoint from which white light emerges as the interaction of all the fundamental light colors, for Goethe, the opposite is true: White light and darkness are, at rock bottom, the only fundamental phenomena, while color emerges due to an interaction of it. In this view, darkness is as real as light, with both representing a natural dichotomy from which all the other optical phenomena can be explained.

What confirms this further is the fact that, generally, colors appear only at the boundaries or edges between light and darkness. See, for example, how the upper and lower horizontal boundaries of the figure above left appear when seen through a prism and compare it with the upper and lower colored spots of the figure right. Only where light and darkness come together can colors arise through the prism: Colors appear when light is extended over darkness or darkness over light. With this way of seeing, one conceives the lightest yellow containing more darkness than white and the darkest blue (or violet) containing more light than darkness. The yellow ‘radiates’ into the white, and the red ‘encroaches’ on the black, while the light blue is ‘drawn’ into the white and the violet is ‘drawn’ into the black. These ‘edge spectra’ display the primary phenomenon in its fullness: Colors arise only at the meeting zones of light and darkness. The same happens for a grey surface over a black or white background, even though the colors will be less intense.

Therefore, colors are not developed out of or driven from light; rather, they can be considered a phenomenon called forth by darkness from whiteness. They are a manifestation or the excitation of light (something reminiscent of the excitation of the quantum fields that represent elementary particles in QFT). Colors are ‘qualities of being of Nature’ or, as he couldn’t fail to express as a poet, the ‘deed and distress of light’.

By this method, one can explain all optical phenomena without resorting to the conventional concept of a refraction index of a transparent medium (the prism) associated with an electromagnetic wave (the colors). The prismatic and color phenomena can be derived even without inventing abstract light rays having diverse refrangibility. Goethe considered the modern idea of the light ray as a useful symbolic tool, a ‘hieroglyph’ that replaces the true phenomenon, which, however, obfuscates its true cognition. From this perspective, it is the modern, scientific, mechanical, and materialistic conception of reality that ends up having a much more transcendent character than this phenomenology, because ideal lines and calculations replace the real phenomena with abstract (almost Platonic) mathematical forms–that is, mistaking the map for the territory–what Whitehead called the science’s ‘fallacy of misplaced concreteness’.

Moreover, searching for the underlying principles by repeated experimentations with different optical semi-transparent media and observations, Goethe noticed how, for example, looking at a white (dark) background through a darkening (light-flooded) turbid medium leads to a yellow to red (violet to blue) coloring. The interplay between light and darkness as the primal phenomenon that originates colors can be reduced to the following:

Light through darkness —> yellow–red

Darkness through light —> violet–blue

Light and darkness in balance —> green

Armed with these principles of his color theory, Goethe went further in applying them concretely to explain the sky’s coloring. The blue color of the sky at noon and the yellow/red/orange sky at sunrise or sunset can be explained as the tension between the darkness of the sky behind the atmosphere in space (the sky in space appears completely dark; ask astronauts) and the sunlight-flooded medium (the Earth’s atmosphere). When the Sun is at its highest point over the horizon, and the atmosphere layer flooded by its light is thinner, the darkness dominates light, leading to the blue (or indigo or violet) color becoming visible. Meanwhile, when the Sun is low above the horizon, and the atmosphere layer flooded by its light is thicker, the light dominates darkness, resulting in a yellow (or orange or red) coloring. The same phenomenon is also explained by modern physics, depending on the traversed thickness of the atmosphere but, of course, with an entirely different and much more complicated process that involves the scattering of light (so-called ‘Rayleigh scattering’) and the atomic absorption and emission lines of the substances contained in the atmosphere.

Phenomenology: A Relic or a Legacy for the Future?

“If a science seems to falter and, despite the efforts of many active people, does not seem to move from the spot; then it can be noted that the fault often lies in a certain type of imagination as to how objects are conventionally seen, in the once adopted terminology, to which the great crowd unconditionally submits and follows and to that which even thinking people escape only in individual cases.” - J.W.v.Goethe [1]

However, Goethe’s color theory isn’t that simple. These were only a few examples, a brief sketch of a more elaborate phenomenology.

Summarizing Goethe’s approach, we could say that it is about a vision in which we recover an intimate relation with Nature, between its phenomena and our sensory perceptions, and between things, plants, animals, and humans. But it would be a mistake to misinterpret the intuitive Goethean approach as non-empiric and non-rational. He was not alien to forms of precise and meticulous observation, description, ordering, and categorization. It would also be a misconception to see Goethe as averse to other forms of investigation. He accepted the other sciences like anatomy, physiology, chemistry, orthodox zoology and morphology, natural history, etc. What did come under his severe criticism was the fact that empiricism stopped there, at a purely quantitative, anatomical, and descriptive level, without an attempt to find the ‘Ariadne thread’ through the maze of natural shapes and figures (‘Gestalten’). By doing so, we dissect life into particularities and miss the wholeness of the living beings.

He also cautioned about jumping to conclusions by performing a single experiment. One experiment, however crucial, can’t be enough. Phenomena must be understood and explained only after a long series of experiments and observations that have to be seen in their entirety as an expression of a state of things that cannot be revealed by a single and limited fact. Every experiment must be connected and united with others. Only by seeing all the similarities and gentle divergences taken together can we frame a hypothesis describing the true nature of the so-observed phenomena. Nothing in the living Nature happens without the existence of a connection with the Whole, and we would incur an extremely limited if not entirely false conception by focusing on a single isolated fact without realizing the connection of all the phenomena. In his words:

“One cannot be too careful, therefore, not to conclude too quickly from experiments. For in the transition from experience to judgment, from knowledge to application, is the passing border where the inner enemies lie in wait for man: Self-suggestion, impatience, rashness, complacency, stiffness, thought-form, preconceived opinion, comfort, carelessness, changeableness, and whatever the whole host with their retinue may be called, all lie in ambush here and suddenly overpower both the acting man of the world and the quiet observer who seems secure from all passions.” [1]

It is only with this spirit, where we have to perform a large number of observations and experiments that connect with slight variations, and by adopting different points of reference that we can gain a ‘higher kind of experience’ of what is seen and that thereby emerges as a single cognitive phenomenon departing from a variety of natural phenomena. Otherwise, we will be prone to picking out the single observation, fact, or empiric datum that confirms our biases and false premises while leaving out all the other findings—something we believe is a quite actual state of affairs in modern science, as we amply documented with the mind-brain fallacy of modern neuroscience.[3]

With this intention, Goethe developed his theory of metamorphosis. His aim was to find the ‘general typus’ in complete and matured animals. We should take a higher standpoint of understanding that contemplates Nature’s formative diversity and expresses itself in a creative impulse of a multiplicity of forms. It is precisely this huge variety of forms and its parts that expresses the ‘One-Form’ and the whole power of nature, triggering in us the non-sensorial sense of bewilderment and awe. What our ‘inner sense’ captures through our outer senses is the formulation of only one ‘typus’. Though Goethe embraced an evolutionary perspective, he didn’t see the animal as the original form of man; rather, both man and animal were the creation of the same original form invisible to the purely analytical sense-mind. It is about developing a general picture in which we take a higher standpoint where man naturally appears to be subordinated, not the peak of the natural processes. Then we can apprehend, in a sensorial and non-sensorial single vision, a general character inside an organized world of connected elements and ruled by a universal harmony of all the parts of a living being. This puts us into the right cognitive status through which we should observe the developing forms and phenomena of Nature.

Let us turn back to the question: why was Goethe’s approach not as successful as Newton's? One of the possible answers is that, because a purely phenomenological explanation relies only on qualitative observation and description that excludes any quantitative mathematical formalization, it could not develop into a practical science, while Newton’s physics lends itself naturally to a practical and technological utilization via mathematical tools. Building skyscrapers requires precise calculations to guarantee static and structural stability. Building electronic circuits would be impossible without quantification of its electric current-flows while launching a satellite into orbit can’t succeed without knowing Newton's law of universal gravitation.

Moreover, Goethe’s phenomenology is a fascinating science that tells us, from another perspective, how the phenomenon we observe works, but it might not look like a particularly useful methodology to predict new phenomena. Galilei’s and Newton's scientific approach could predict the existence of a planet (Neptune) that nobody suspected to exist before, and led (much later) to Maxwell’s equations and the modern theory of light, which predicted that visible light is an electromagnetic wave and that it even extends beyond the visible spectrum—that is, into the infrared or ultraviolet domain. Modern optics can equally account for all the optic phenomena that Goethe described, though complicated calculations are sometimes necessary—a fact that, yet again, shows that science was never driven by principles of parsimony but, rather, by the predictive and practical effectiveness of its way of seeing and describing reality. If scientists would really adhere systematically to principles of parsimony, Goethe’s approach would have had to be preferred by far over the conventional, rather complicated physical models. A science that looks for archetypes, primal phenomena, or a unitary vision of Nature and reality making testable predictions has yet to be born.

And yet, we will see next that it is a science that has indeed a still undiscovered predictive power that several conventional scientists even use subliminally, resorting to a higher-mind sight without being aware of it. It is something on its way to being discovered that will show us how Goethe found the tale of the lion and was still struggling for completeness.

But the excitement for the dawn of a new philosophy of Nature, what we nowadays call ‘science’, was far too great to allow the subtle call of a finer cognition to be noticed. Nevertheless, Goethe’s way of doing science remains a contradiction-free alternative to the present paradigm. Branding it as a mere historic remnant of a nostalgic humanist would be a superficial and blind understanding of its merits and the nature of his investigations. This complementary way of conceiving and practicing science may have to be developed further to reach the status of a convincing and viable alternative to Newtonian science. We tend to believe that it has met the same fate as the natural philosophy of the ancient Greek philosopher: Hellenic culture came very close to the modern scientific approach. Aristotle, Democritus, Aristarchus, Ptolemy, and several other ancient Greek philosophers were clearly making their way towards a quantitative and empiric science, though they were not fully there yet. Unfortunately, their tradition was discontinued and forgotten for about fifteen centuries. We dare to maintain that Goethe’s approach may have suffered the same fate. It was still not a full-fledged science and had to cope with the invasion of an industrial revolution and the increasingly materialistic and sense-mind-based age of the Enlightenment, which quickly swept it aside. We don't have a crystal ball and can’t predict the future but contend that the last word has still not been said.

However it is, Goethe’s theory of colors is only an example of how a highly mathematized, exact science like physics also has its non-mathematical, qualitative side. Modern physics, especially the theoretical physics of the last century, is a manifestation of Nature’s quantitative aspect reflected by the intellectual mind of our species. It is not surprising that mathematics is so effective in describing natural phenomena: The materialistic and analytic sense-mind, which we call reason, is in its essence a cognitive tool that deals with differences and distinctions and that discriminates between things. By adopting a way of seeing that, instead of seeing the whole, distinguishes in space and time by separating things numerically, it obviously can see nothing other than a mathematical universe. But the mind is also able to differentiate between qualities. Adopting the phenomenological way of seeing the very same reality will then present another face, that of a phenomenal qualitative universe that, if we transcend the divisive tendency of the sense-mind and see comprehensively, will reveal its unitary nature as a display of primal phenomena. The emerging unity appearing from the bottom-up cognition of the reductionist sciences, which bind and connect the pieces only by means of external relations, fails to recognize the ‘relationless’ Unity of which they are only an expression.

Natural phenomenology does not negate, let alone replace the former approach, but adds a new dimension to it. It is the rational reductionist scientific materialism which assumes that its own way of seeing is the only right and possible one and, more or less subconsciously, holds even the analytic mode of consciousness as that which knows the world as it is in itself as if a human’s scientific way of seeing is the last word of the cognitive evolution of the species.

This new way of seeing could play the same role in the transition between natural philosophy and the empiric Galilean and Newtonian science. The latter didn’t emerge due to new facts but because the human species switched to another way of seeing, to the mathematized reductionist empiricism. Similarly, a new phenomenological science may well emerge, not because of some groundbreaking discoveries of new facts but, rather, because the human species may again be bold enough to take a step further, namely, that of switching to a holistic mode of consciousness. Once we realize how the change in the way of seeing also implies a change in what is seen, this becomes an unavoidable and logical conclusion. As H. Bortoft succinctly wrote:

“Now, it is usually supposed that this is the only kind of science which is possible, and hence that any alternative to the analytical perspective can only come from outside science. But another possibility is that there could be a transformation of science itself which would be the development of a different kind of science that is not only analytical. We have seen how Goethe showed the way toward such a science and that this is not an alternative, in the sense of seeking to replace analytical science, but a way of being complementary to it. The point is that analytical science is really a one-sided development, and it is this one-sidedness which needs to be removed. So the aim is not to replace one science with another but to overcome a one-sided development that is historically founded and not intrinsic to Nature in the way that it is imagined to be. This new kind of science, which is holistic instead of analytical, is the science of the wholeness of Nature.” [2]

[1] J. W. Goethe, Naturwissenschaftliche Schriften, S. V. -. 2016, Hrsg., 1790.

[2] Henri Bortoft, “The Wholeness of Nature: Goethe's Way of Science,” Floris Books, 1996.

[1] He did this not really with white light because it is quite complicated to produce a perfectly white source but, rather, with sunlight. These technical details, however, aren’t essential here.

[2] Readers are invited to find a simple optical prism and perform this and the following experiments by themselves. Experiencing these phenomena from a first-person perspective can be quite impressive and conveys a much more authentic understanding of them than a written description can do.

[3] In fact, we presented not just one fact but a whole series of facts and invited the reader to see them in their entirety. It is by this wholeness of all ‘cerebral phenomena’, seeing them comprehensively, that the physicalist mind-brain doctrine becomes untenable.