Can Divine Action Operate in a Clockwork Universe?

Believers Fail to Explain How God Intervenes in a Mechanical Universe.

For anyone who believes that God acts in the world, a fundamental question arises: How does that happen? The universe, as far as we can tell, operates according to consistent principles. From the motion of galaxies to the firing of neurons, every observed process follows patterns described by physics. If this is true, then divine action cannot simply override or ignore these laws without plunging reality into chaos.

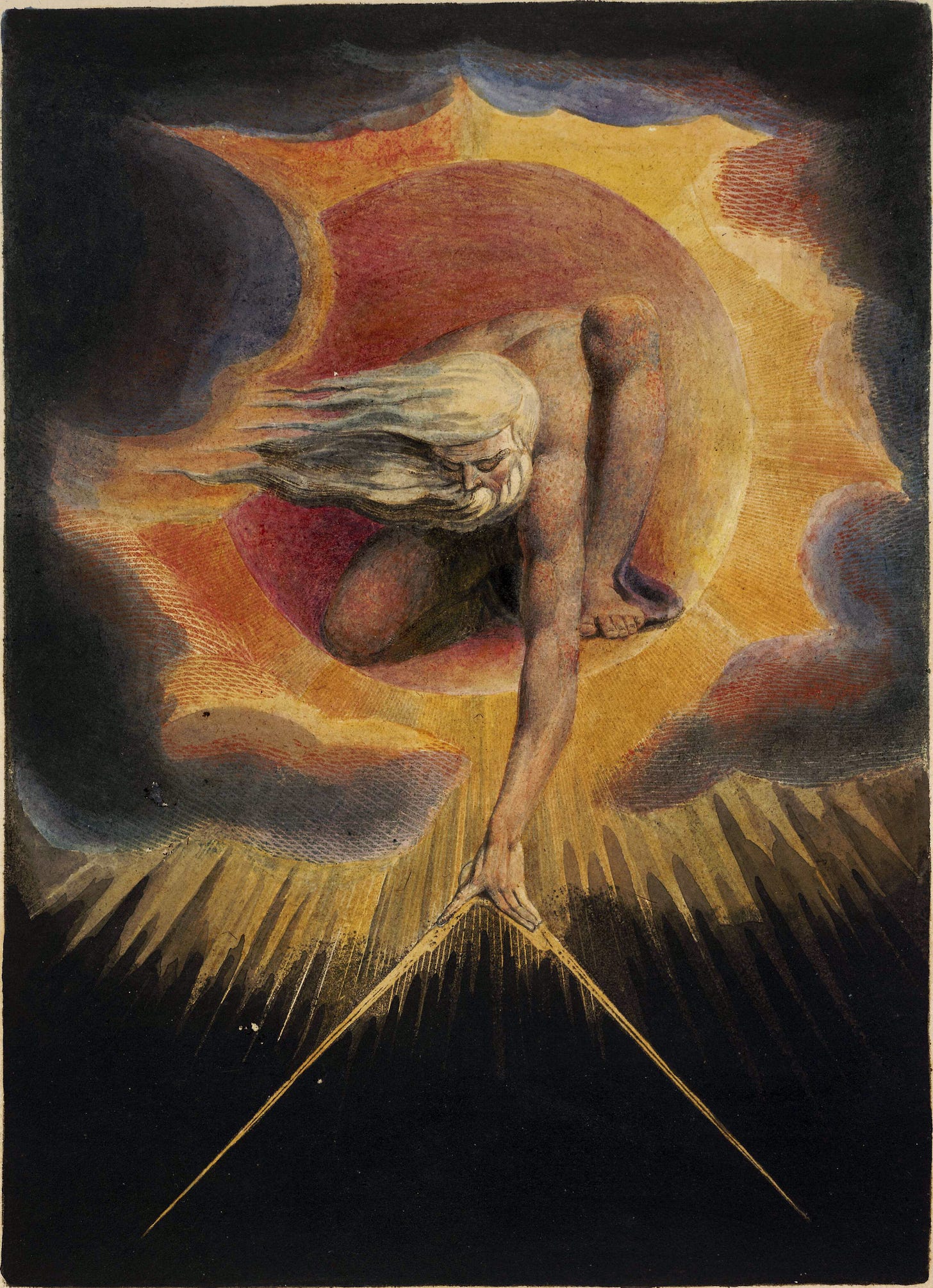

In the 17th and 18th centuries, the success of Newtonian mechanics encouraged a view of the universe as a perfect machine. If every event could, in principle, be predicted from prior conditions, then the cosmos was like a giant clock set in motion at creation. This gave rise to ‘Deism,’ the idea that God created the universe with its laws but no longer intervenes. Pierre-Simon Laplace famously declared that if a being—the so-called ‘Laplace demon’—knew all the particles, its properties and its initial positions and velocities at one moment, it could predict the entire future—a claim often taken as the manifesto of determinism. In such a clockwork model, divine action after creation seems unnecessary or impossible.

Many believers respond to this issue by appealing to mystery. They say “God’s ways are beyond our understanding,” or “God acts by Grace.” While true in one sense, I believe this answer avoids the question. If divine action interacts with the physical world—causing an illness to heal, guiding history, or answering prayer—then something must happen at the physical level. Energy, matter, or information must be affected. Some purely deterministic mechanism based on our conventional notions of cause and effect can’t be true. To affirm that God acts but deny any interest in the how leaves an explanatory gap. It is a refusal to engage the question and the mystery remains.

The universe, as science reveals it, operates according to consistent physical laws that don’t leave much space for trans-material and/or trans-rational interactions between a no better defined spiritual realm and the material world. Consider the orbits of planets, which follow trajectories determined by Newton's laws of universal gravitation. No exceptions to this rule have ever been observed. God seems to have no authority over the movements of planets. If, instead, that is the case, then the burden of proof rests with the believers. How can divine influence enter a system that appears closed under a strict principle of cause and effect that admits no exceptions? Can God act without breaking the very laws that make the universe coherent?

But the universe revealed by modern physics is more subtle than the old deterministic picture. The universe is not the rigid clockwork that Enlightenment thinkers imagined. It contains openness, complexity, and unpredictability—features that some interpret as space for divine creativity. The rise of chaos theory, quantum mechanics, and complexity science suggests that the cosmos may not be a rigid machine after all. Does this openness provide a way for divine action? How could a spiritual being interact with a physical matter? How can an immaterial God interact with a material world?

So how can God influence the world while keeping its lawful structure intact?

About two decades ago, the theories of theoretical physicist, theologian, and Anglican priest John Polkinghorne gained popularity, suggesting that Heisenberg’s uncertainty principle opens the door to divine action. This uncertainty in quantum physics implies a universe governed by probabilistic behavior and inherent randomness—an idea that did not resonate with Einstein, who famously stated, “God does not play dice.” According to this perspective, unpredictability is not merely a reflection of ignorance but rather an indication of intrinsic agency. It conceals other causal principles that operate in the universe. If the universe is fundamentally random, divine influence could potentially operate within quantum probabilities, guiding events in ways that align with natural laws. This influence would be subtle yet genuine.

It presents an approach to divine action that emphasizes a different understanding of God's role in the universe. We should not envision God as a supernatural "intervener" who occasionally suspends natural laws. Instead, we should perceive the universe as fundamentally open and layered, with new properties emerging at higher levels of complexity—such as life, consciousness, and culture—that cannot be reduced to mere physics. In this perspective, divine action unfolds through these emergent processes, functioning within the indeterminacies and flexibilities that nature inherently offers, rather than overriding physical laws. Quantum uncertainty, chaotic dynamics, and the openness of complex systems allow for divine influence without disrupting causal chains. God acts in every event, yet never in a manner that contradicts scientific principles.

This grounds God as being both immanent and transcendent. This framework enables God to be intimately present in creation, influencing it from within rather than manipulating it from the outside. An understanding that provides the most coherent affirmation of divine action in a scientific age, portraying a God who operates through the dynamic creativity of the universe itself.

Others, such as Philip Clayton, Ian Barbour, Arthur Peacocke, Robert John Russell (and what about good old A.N. Whitehead or T. de Chardin?), made similar claims. They argue that God does not need to "break the rules" of physics but can instead operate through the flexible structures inherent in the cosmos, resorting to intrinsic indeterminacies.

However, the catch is that this is easier said than done. To my knowledge, none have provided specific details that could be considered a scientific theory; their ideas remain vague. There are intrinsic limitations and logical reasons that stand in the way of these speculations, which cannot be ignored. If divine intervention were to occur, with God determining which of many possible quantum outcomes takes place in an ‘open’ universe that is not causally closed, it would alter the probabilistic laws of quantum physics, resulting in observable anomalies.

It is like trying to cheat at a lottery. In a fair lottery, every number has an equal chance of being drawn, and over time, their frequencies should roughly balance out. Cheating—that is, intervening in the random process—disrupts these patterns and becomes evident because it violates fundamental statistical principles. Certain numbers may appear far more frequently than expected, while others may show up less frequently, resulting in imbalances too significant to be random. These anomalies quickly become apparent as the number of draws increases, making systematic manipulation easy to detect through statistical analysis. However, nothing like that has ever been observed. Those who use quantum randomness to justify divine agency never address the question of how God intervenes in the cosmic lottery machine without being caught red-handed.

Another persistent weakness among most of these philosophers, theologians, and scientists is their adherence to an exclusivist Christian theological perspective. To be taken seriously when making metaphysical claims related to science, one must transcend their own religious affiliation and early educational conditioning, adopting a worldview that surpasses individual religions or local cultural belief systems. For reasons beyond my understanding, we remain utterly unable to achieve this in the globalized 21st century.

Today, these ideas are further complicated by a plethora of pseudo-scientific theories that invoke quantum physics to explain concepts like quantum laws of attraction, telepathy, and quantum healing, among other forms of "quantum woo."

Conversely, naturalists also fall short when they uncritically accept the peculiar randomness of the quantum world. Simply asserting that it is "just random" does not lend them greater philosophical credibility. Physicists will tell you that quantum mechanics is a "theory without hidden variables," which means nothing and essentially translates to "shut up and calculate."

Thus, to my knowledge, no satisfactory (classical or quantum) theory has been proposed that can explain how divine causation, if any, operates within the universe as described by science.

Why is this important? Because the credibility of faith in a scientific era hinges on intellectual honesty. If believers assert that God intervenes in history, heals the sick, or answers prayers, they must confront how these beliefs coexist with a universe governed by physical laws. If the universe operates according to established laws and God acts within it, believers have a responsibility to provide an explanation—at least in principle—of how such divine actions could occur. Merely stating that “science cannot explain everything” is insufficient.

Conversely, when philosophical naturalism asserts that the universe is fundamentally meaningless, aimless, and indifferent to human existence, and that there is no divine action, it is also making a statement based on faith. Ultimately, it lacks substantial philosophical depth as well.

What is needed is a dialogue that respects both theological integrity and scientific understanding. Up to this point, there has been little more than wishful thinking and wordplay.

The subscription to Letters for a Post-Material Future is free. However, if you find value in my posts and would like to support my work, you can make a small financial contribution by buying me one or more coffees. You can also support me by ordering one of my books or follow one of my online courses. Thank you in advance!

A timely post for me, since I was just talking with someone about these very issues.

"Thus, to my knowledge, no satisfactory (classical or quantum) theory has been proposed that can explain how divine causation, if any, operates within the universe as described by science."

Right. The key phrase here is "as described by science". I agree there's a lot of confusion on both sides. Theists evoke quantum indeterminism or fine tuning arguments or other physical-law breaking phenomena, but these types of arguments face the same problems as the old divine clockmaker analogy. These theist arguments take a scientistic framework for granted and reason more or less inductively, drawing sweeping generalizations from necessarily limited scientific "conclusions". Interestingly, both sides agree on the inductive reasoning, and yet both sides happily point out the epistemological precariousness of their opponent's reasoning without seeing that their criticisms apply equally to their own position.

For instance, in this video, Sean Carroll applauds the fine tuning argument for "playing by the rules" and calls it the theist's best argument. In other words, he's insisting that explanations must be scientific:

https://youtu.be/KjRkOzKy0Iw?si=RYMMLpCjaeGhlYI0&t=125

From there he proceeds to knock down the fine tuning argument on the basis of epistemological uncertainty, either because science isn't complete or because we don't have the privilege of a god's eye view. (He asks: how do we know what physical parameters are required for life to exist? First we have to define life, etc. Then he evokes the incompleteness of science by saying, "until we know the answer, we can't claim they [physical parameters] are finely tuned".) But he fails to see his arguments cut both ways.

I would rather question his assumption that anything outside science's purview simply doesn't count as knowledge. Where is the scientific evidence for that? It's not just an unsupported claim that goes beyond what science can actually tell us about the world, but an epistemic overreach, one that's all too common and often goes unchallenged. And I disagree with him in his opinion that the fine tuning argument is the best argument theists have—I think it's one of the worst. I think these types of arguments often concede too much to naturalism at the outset and get stuck in the same quagmires.

It's not terribly popular these days to suggest we approach explanations of the physical world with the appropriate epistemic humility required for the subject matter. And so now whenever I challenge physicalism, it's assumed that my views are no different from someone like Phillip Goff's, who said on Twitter, "According to our current best physics the universe is fine-tuned for life. It's astonishing how many people feel able to deny the science on this." He was trying to be provocative, of course, and he succeeded in that. But I don't think that's the best approach. It undermines the larger point Goff himself made in one of his books or articles (I can't remember which) that modern science gained its usefulness and predictive power by cutting reality down to size.

Of course, this point has been made many times, and maybe it needs to be made clearer that science really is a limited kind of knowledge. But how? What more can be said? I agree, I don't think it'll work to say science can't explain everything, or science can't explain x—reduction is always possible, in principle, after all. It won't work to say science proves god or some immaterial thing exists—your opponent will always see nothing but a duck where you see an illustrator drawing a duck-rabbit with pen and paper. What can we do but point emphatically and say, "There's more than the duck! See!?"

We talk grandly about a "clockwork universe," but I think an example may be helpful.

This afternoon, while coming back from the beach, I fell off my bicycle. A car was approaching on the narrow dirt road, and I was well to the side, where the red soil had piled up from a constant wind. My hat blew off, and I braked hard, only to slide in the loose earth. As the bike came to a halt, I began to fall.

There are two things you can do when you begin to fall off a bike. You can fight to stay upright, or you can go along. Being an old fellow, and not as strong as I used to be, I chose to go along. As a boy I used to practice falling -- it was an exercise in a judo book I owned -- and now I put this experience into practice, relaxing my body into a cushioned fall on my left side. The bike proved to be an encumbrance, and I sustained a slight bruise on my inner thigh, but overall the manoeuvre went well. I disentangled myself from the machine and waved to the driver, calling out, "I'm fine!"

From the point of view of a clockwork universe, we can look for the causality here. The physical forces that were about to take me down could be calculated with some precision. The trajectory of my fall, the point where I would hit, even the marks left in the dust, could be foretold in advance by the tools of our present science, to within fairly tight tolerances.

But extending this story, and looking deep into my brain, these same tools are expected to provide a much deeper account that includes why I chose to fall, rather than struggle to stay upright. This kind of prediction is not within reach of our present science. Nevertheless, we hold confidently that we could do it in principle. The account we give is one of inputs and outputs: my brain received information about my probable trajectory, and based on its previous experiences, that is to say the accumulation and configuration of white matter up to that moment in my life, sent outputs to my limbs that resulted in me falling off.

But something is missing from the account: namely, the idea that I might, at the risk of pulling an aging muscle or two, have fought to stay upright, to avoid the bruise and to spare my dignity, to land with my feet planted astride the frame. This scenario would have been equally within the laws of physics. Had I made the attempt, the outcome could have been predicted, to a reasonable degree of precision, with our present tools. It might have been one of failure, but the mere jerk of the handlebars or twist of my torso would nevertheless have led to a different result. And this result would not have required any violation of causality. The only difference between the many physically possible scenarios following this instant in time concerns the amount of strength or resistance I decided to muster.

For all the successes of our current science, the proposition that it could have predicted my decision remains a fantastical one. The model of clockwork has been pushed far beyond any legitimate claims to power. It is quite conceivable that in my brain, or more likely my entire body, some complex of quantum manipulations inserted itself, deviating in subtle ways from the main chance through millions or billions of probabilistic spikes, calculating in unfathomable ways what to do about the immediate future, and then making a choice. The clockwork effects would have followed either way; but the machine would have been, as it were, tilted.

The clockwork model resists this organic interjection, and even has the temerity to put it down to foolish and fantastical notions of "free will," of which the thoroughly rational thinker must be disabused. But in its failure to acknowledge the vivid reality that is everywhere encountered at moments like these, it is the clockwork account that begins to look foolish and fantastical.